Mary and Joseph mess up. Their only child, and they lose him. (read Luke 2:41-52) Aren’t parents supposed to know where their kids are, at all times?

Now, of course, this stuff happens all the time to the best of us—in large crowds, at amusement parks, sports stadiums, Disney World, the mall. Unintentionally we make mistakes. Each of us can likely relate to a time when we got lost and felt abandoned by our parents, and how that felt. Or, how as parents we lost track of our child. And how that felt. The fright. The embarrassment. The shame.

Maybe it’s a comfort to know that even Mary and Joseph parents of the Christ child didn’t get the parenting thing right, on occasion. Today, we would communicate that in social media as #parentingfail.

I’m reminded of the popular Christmas movie, Home Alone, when a family plans a European vacation for Christmas. The relatives all arrive for the big event. But in all the commotion the youngest son feels slighted. Expressing his frustration inappropriately, he is punished and sent to a room in the attic.

There, in a fit of anger, he wishes that his family would go away so he could be all alone. The next morning, in their rush to get ready and leave for the airport, the family overlooks the little boy in the attic. They get to the airport and board the plane, all the while believing he is with them. The boy gets his wish when the next morning he finds himself home alone.

The twelve-year-old boy Jesus experienced the feeling of abandonment by his parents. Perhaps this was a foretaste of the abandonment of the cross he would experience at the end of his life. It appears Jesus knew already from a young age what it felt like to be a human being. It appears he learned to accept the follies and misgivings of the human condition. For, he experienced it himself. At the end of the story, he felt the joy of being found and of not being alone anymore.

In the Judaeo-Christian tradition, the temple was a sign of God’s eternal presence. And so we have a clue as to why this story from Luke is read on the First Sunday of Christmas. Because, without the temple, how else would this story fit? After all, Christmas is about the birth of Jesus. And this story is about Jesus on the verge of adulthood, his ‘coming of age’ story from the bible.

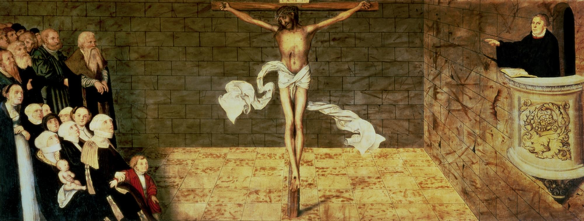

Jesus was found in the temple, engaged with the learned in conversation about God. In his childhood experience of abandonment—in the midst of it—he was still in God’s presence. He was found in God’s presence.

Christmas is about the promise of God to be with us. It is about the grace and gift of God-with-Us, Immanuel. Immanuel is the name given to Jesus by the angel in the Christmas story. It is a name to give us hope.

God is with us, even in the darkness of grief. God is with us, even when we feel abandoned. God is with us, even when we are lost and forsaken. God is with us, even when we are confused and don’t know what to do. God is with us, in all our losses, pain and especially in our suffering. That is why this story, I believe, is included in the Christmas repertoire year after year: To remind us of this holy promise of hope at the darkest time of year: God is with us.

It feels like once we celebrate those first few days of Christmas, time seems to thrust forward in leaps and bounds. At one moment, we are cooing with the barn animals at the baby in the manger and singing hallelujahs with the angel chorus over the fields of Bethlehem.

And the next, we actually fast forward over a decade in the story of Jesus to this temple scene when he is almost a teenager. The Christmas message catapults us from the past, into the present and towards the future in a kaleidoscope of events that unite in the meaning of God-with-us.

A gift-giving tradition in our family is the exchange of books. I just finished reading a fiction which told its story by shifting forward and backward in time. In reading through the book from beginning to end, there were times when it felt a bit dis-jointed, where I asked myself especially early on: What does this detail or this person have anything to do with the story? Why is the author spending so much time and several pages describing this particular scene or detail? How does it all fit together?

This technique, of course, kept me hooked. I was committed to the journey. I had to trust that in the perplexing ‘set-up’ the author was providing, there would eventually be a satisfying ‘pay-off’. And I wanted to know, and feel, the resolution to the mystifying issues, sub-plot lines and character developments. I had to trust and hope that the longer I stayed with it, at some point, there would be some satisfaction to the bemusing chronology of the storytelling.

People will often say, there is a reason for everything. Even when bad things happen, they will say there was a divine purpose. I would sooner say, in everything that happens—good and bad—God is present, and there is reason to hope. Because we don’t know the mind of God.

As soon as we say ‘everything has a reason’ we presume our suffering is a consequence of our not knowing. But knowing ‘why’ is not our business. We cannot comprehend the fullness of the divine mystery and purpose. We can’t really pronounce on what God is up to in the evolution of reality and history. We can only make the next step. Our task is to become aware of God’s presence in all our circumstances.

In hope.

If we are not a people of hope, we are not human—just animals scavenging for survival and reacting to impulse. If we are not a people of hope, we are not the people of God who are called to see beyond the circumstances of the desert and darkness of this world with all its suffering.

In hope, time is really irrelevant. In hope, the past and future collapse into the present moment. That’s where we live, anyway. This time of year is not well-behaved, neat, and orderly. To be faithful in this time-tumbling season is to stick with it despite the disorderliness of our past, present and future, and not just give up.

We can appreciate the good in the past and can anticipate the good that is promised in the future. We can hope that no matter what lies before us or what happened behind us, there is good that still awaits. There is good that is here.

God is here. God is present. God is involved, now. That’s the meaning of Christmas—God is now with us, Immanuel. For now, and forevermore, God sheds tears and rejoices alongside us. God walks with us on this journey and will never abandon us in God’s love.

Hope is what keeps time. Hope is what connects the past and the future into the marvel of the moment. A moment in time infused with grace.

Where does hope reside in your life? In what activity? In which thoughts? What feelings are associated with hope, for you? How do your thoughts, your actions and your feelings reflect hope today?

May you be open to the blessing of God’s presence, in the New Year.