After receiving God’s blessing and vision at his baptism, Jesus is led into the desert. He is led into the wilderness by the Spirit of God where he spends the better part of a month and a half (Matthew 4:1). That’s a long time.

Who would go there? And for what purpose? Why would anybody, especially right after receiving a holy calling and divine blessing, wander into wastelands full of danger and unpredictability?

You would think Jesus would immediately go to launch his mission of healing and proclamation. You would think Jesus would go directly from the Jordan river where he was baptized to the highways and byways, the street corners and the seats of power around Jerusalem. Which, he eventually does.

But instead, the first thing he does is go alone into the desert. For a long time.

The season of Lent is upon us. The long weeks leading to Easter have been described as a pilgrimage, a journey (Pope Francis, 2025). Martin Luther opposed the concept of pilgrimage in the medieval sense because he deemed going on pilgrimage as “works righteousness”. But Luther kept Lent. He saw the season of Lent as an opportunity to reflect on the Passion and suffering of Christ.

Today Lutherans will frame the 40 days of Lent as a “journey to the cross” or a “spiritual journey,” a concept that aligns with Luther’s theology of the cross.

It is on the cross where God is revealed most clearly in Jesus’ suffering. The heart of the Gospel is the mercy and grace for humanity that God experienced in Christ crucified. The intention of Lent is to focus on the path Jesus took through the cross to the empty tomb. Lent acknowledges that the only way to a good, new beginning is by embracing and working through the losses in our lives. This journey through the desert – the cross – is not easy. It’s work, moving forward.

Another way of describing it is that it’s always three steps forward and two steps back, between the cross and the empty tomb, never a straight line. But it’s the backward that creates the knowledge and the energy for the forward. We have to allow it. The desert is necessary for our growth.

We have an aversion to the cost of this journey. And that’s why we avoid it. We distract ourselves with efforts to win and achieve glory. We are inclined to skip Good Friday and go straight from singing the hosannas of Palm Sunday to the alleluias of Easter Sunday. We would rather avoid the desert experience.

What’s this business of God dying on the cross, anyway, suffering defeat at the hand of Jesus’ enemies? Who would go into the desert, anyway? Who wants to associate with losers?

Jesus does. And many did and still do, follow him there. Who were these first desert mystics and contemplatives, as we’ve called them?

I think we have this notion that the early desert mothers and fathers were some sort of super saints or perfected hermits. We falsely presume these desert Christians were pious followers of strict religious rules who had purged themselves of all fleshly desire and pleasure. That is incorrect (Colón Delay, 2026).

In the year 313 of the Common Era and the Edict of Milan, Christianity became the official religion of the empire. While the edict granted religious freedom and presumably ended the persecution of Christians, many Christians at the time were concerned with how becoming yoked with political power would affect the message and meaning of Jesus Christ. Beginning in the 4th century, many Christians who wanted to genuinely live out the promises of Christ and deepen their walk with God left the empire, so to speak.

And so, they went out into the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Arabia. These were women and men, rich and poor. Some of them had been working in royal courts, and some had been murderers. Some were people of high esteem in society while others were viewed by society as scoundrels, persons of ill repute, outsiders, misfits (Acevedo Butcher, 2026, February 15).

By shedding their securities, and courageously moving into the unknown and potentially dangerous desert they knew they would be transformed by the experience of trusting in the ever-presence of God alone. On the journey itself, without necessarily knowing the destination, they knew they would be changed for the better.

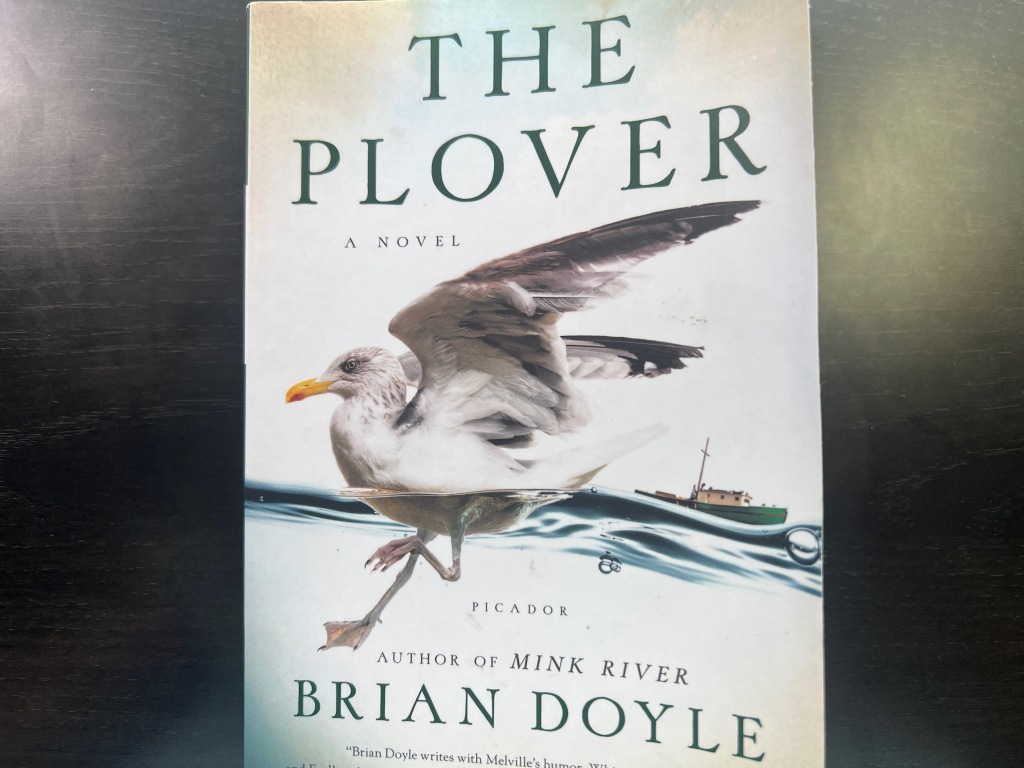

From the desert into the open sea.

Some of the first monastic missionaries, from the Celtic tradition, would put themselves out in a boat – without oars. These boats were built to be sturdy enough to sustain a long voyage, but they were still small and could not be called ships.

Trusting the currents and the winds, the voyagers would simply drift until they landed where God had called them to be. For them, trusting God required a complete surrender to God’s will in the present moment. While a ’pilgrimage’ has a clear end in sight, a ‘peregrenatio’ does not. It is a wandering or drifting without a known destination (Valters Paintner, 2018).

Who would go into the desert or out onto the open sea? A people following Jesus. A people wanting and preparing for meeting the risen Christ who travelled there himself, who had experienced the challenges and temptations of going on this kind of journey.

I’ve been on a journey during my practicum. But this journey really started when I began the master’s degree program in counselling / psychology over two years ago.

Early on it felt to me like a pilgrimage with all the attending ups and down and unexpected twists and turns along the way. Early on it felt like as long as I stayed on the path I would eventually arrive at the destination – which was the end of the course work and this practicum. And then, it would be back to being the same it was before I started the program.

As the journey continued, however, the experience caused a shift from that of pilgrimage to peregrenatio. I knew and trusted it was God’s leading because every step of the way was validated, and I was finding traction in moving forward.

But I was growing more and more unsure about exactly where this was leading me. I was asking more questions about the purpose of the journey.

At the same time I was beginning to sense how I was growing through the experience itself. The end wasn’t as important as the becoming.

The congregation, too, has been on a journey these past several months. You didn’t know what this experience would be like when we started on this journey last Fall. What have you learned about your relationship to this congregation? With God? What events, developments and experiences during this time stand out in your memory? And which of these events or experiences align closest to what you value?

The journey itself changes us – our minds, our perceptions, our awareness of who we are becoming. We are like the monk in the boat on the peregrenatio, drifting out on the sea, surrendering to the will of God, not knowing exactly the destination but hanging on, nonetheless. How different are you by the end of this journey than you were at the beginning?

So much on this journey calls us to pay attention to the present moment, not ruminating about the past nor worrying about the future. When you don’t have control over the outcome, you will need to learn to let go and surrender to the present moment and what it invites us to notice. The desert and the open sea call us to ‘stay awake’.

The monk in the boat, not knowing what tomorrow might bring, would be fully alive in the present moment. The monk would be scanning the horizon, paying attention to conditions, aware of what his body needed in the moment, ready to respond without judgement just acceptance to whatever came his way.

Although Martin Luther frowned upon the medieval pilgrimage, he was all about being in the present moment. He is known to have said that if he knew the world would end tomorrow, he would still go out today to plant an apple tree in the ground.

So, too, when we stand at the threshold of an unknown future, we may not know the outcome nor the precise destination of our travels.

But will we notice, as we continue doing what we do, the sprig of new life budding in the ground upon which we stand? Will we see and appreciate the signs of hope and life around us? And they are there! From this hope we are nourished and strengthened for the journey ahead.

Who goes into the desert? Who would go there anyway?

Jesus does, to enrich his own life, to embolden him in his mission and purpose. And we go to follow, this Lent, to prepare ourselves for meeting the new life springing up all around us (Isaiah 43).

Then the devil left him, and suddenly angels came and waited on him.

References:

Acevedo Butcher, C. in Richard Rohr (2026, February 15). Wisdom from the outside: Desert and transformation. Daily Meditations. Center for Action and Contemplation. www.cac.org/daily-meditations/wisdom-from-the-outside.

Colón Delay, L. (2026). The way of the desert elders: How the wisdom of ancient Christians sustains us today. Broadleaf Books.

Valters Paintner, C. (2018). The soul’s slow ripening: 12 Celtic practices for seeking the sacred. Sorin Books.

Vatican News. (2025). Pope Francis: Lent calls us to journey together in hope [Website]. https://www.vaticannews.va/en/pope/news/2025-02/pope-francis-lent-calls-us-to-journey-together-in-hope.html#:~:text=This%20journey%20is%20not%20merely,are%20pilgrims%20in%20this%20life.%E2%80%9D