I surprised myself by how much more reading I’m getting done. More than I had expected. I suppose I underestimated how many audio books I would be listening to while driving up to Pembroke several times a week for my counselling practicum.

But this book I read the old-fashioned way – paper copy in hand (but not while driving, let me assure you!).

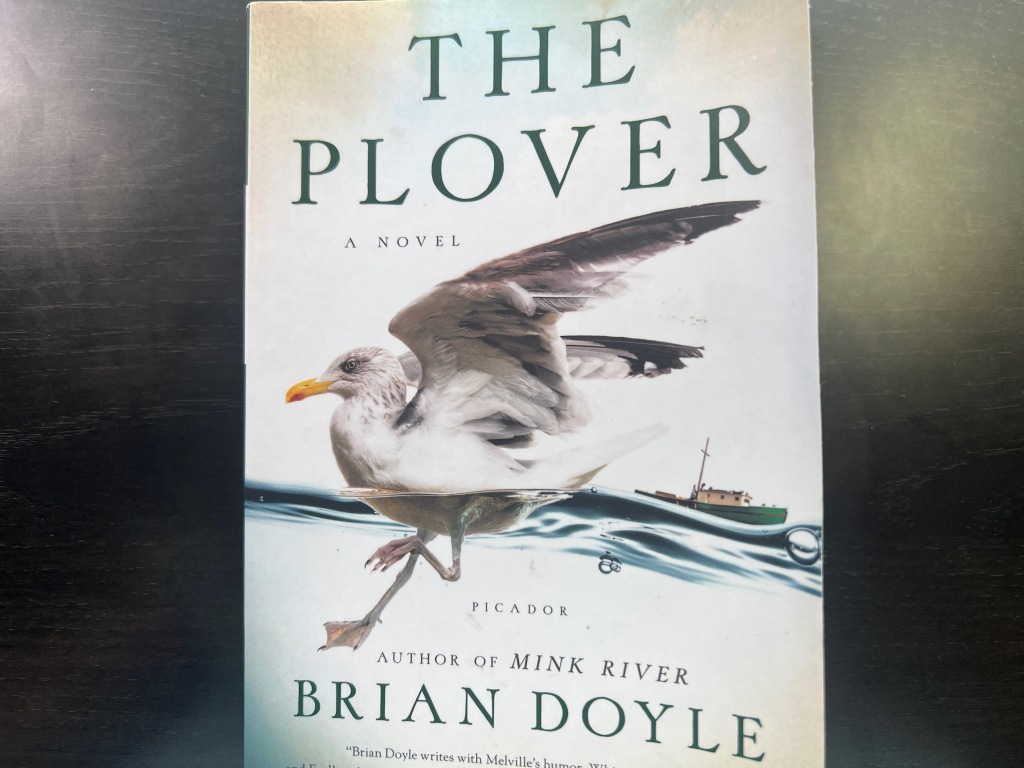

In his book entitled, “The Plover” (a plover is a shorebird), the late Brian Doyle authors a fictional tale about the seafaring travels of Declan and his crew aboard the boat called, you guessed it, the Plover.

One of his crew members is a seagull – yes, a seagull – who accompanies the Plover across the Pacific Ocean. Through storm and gale, calm and quiet, the gull is a faithful companion who, unbeknownst to the crew, tries to communicate to them. Sitting on the deck, or flying 9 feet above the stern, the gull makes remarks about their idiosyncrasies, dangers ahead, islands that exist just beyond the horizon they cannot yet see (Doyle, 2014, pp. 188-190).

This communication only the reader understands. However, Declan and his mates, for the most part, only hear what we normally hear from seagulls – a whole lot of squawking.

There is another character in the story who reflects a little bit of the gull’s perspective, a visionary or prophet you might say, who is not understood. He is referred to simply as the “minister” – a political one.

Before joining the crew, he was violently kicked out of his island home, for proposing an unacceptable vision for his Pacific nation. The minister was rejected because he described a reality he believed in, but for most, unrealistic. He envisioned people actually getting along.

This political vision was largely a dream. It existed over the horizon of human experience. The minister’s vision was the way of non-violence, care and empathy. It was a way of the future just around the proverbial bend of human history. This minister spoke of making the impossible possible (Doyle, 2014, pp. 185-187).

You think it’s impossible that human beings separated by culture, politics and religion can be caring, loving, and compassionate to one another, despite all our differences? Maybe we need to think again.

In the Gospel reading today, we, the reader, observe the story of the rich man from the perspective of heaven (Luke 16:19-31). We see the big picture of rich man’s life, and his life after death.

The rich man’s life is marked by privilege and wealth. His life on earth was the gold standard. His life is what everyone aspired to, what everybody wanted.

Contrast that with his life after death. His life after death comes as a surprise to him, and perhaps to us as well. Why would someone as great and successful and privileged as the rich man end up in hell? This Gospel flies in the face of a belief which rewards the prosperous in which you must earn your worth, where the value of your personal worth is equal to how much money you have. I’m describing the world’s values.

The perspective of heaven, in contrast, announces that while the rich man may have reached the top of the ladder according to the world’s values, he had been, in the end, climbing the wrong ladder.

But the crux of this story is what lies in-between. Between these two realities that only the perspective of heaven can see lies a great chasm. In the story, Abraham tells the condemned rich man that this chasm “has been fixed, so that those who might want to pass from here to you cannot do so, and no one can cross from there” back (Luke 16:26). No one can breach this chasm, this divide. The realm of the afterlife, and the realm on earth are divided. And no crossing over is possible.

We can wrap us this sermon here and say that nothing is impossible with Christ. Christ makes all things possible, against all odds. By miraculous, supernatural means, even. To justify our claim, many of us Christians quote that famous verse from Paul’s letter to the Philippians: “I can do all things in Christ who strengthens me” (4:13). True.

But that verse is not a promise of guaranteed success in every personal endeavor. All things being possible is not a mission statement for doing the impossible according to what I want – my individual desires or longings, or even what the world values.

Rather, all things possible in Christ means all things are possible on earth according to the perspective of heaven, according to God’s vision, God’s future, God’s desire. All things are possible pursuing the righteousness of God, the mission of God.

We may not be in a position now to be able to believe that human beings can relate to one another with empathy, with compassion, with grace and love. You may not believe now that it is possible for people in your life to change for the better, for all wars to cease, for the lion to lie down with the lamb (Isaiah 11:6), for combatants to lay down the sword, for anger to be transformed into a desire for justice.

But maybe it doesn’t matter whether you can believe this claim. Maybe all that matters now is that the idea lies within you now, that the word of grace resides in you like a seed waiting to sprout.

Why?

Because this bible story from Luke is not over, on different levels. First, we don’t know whether the rich man’s brothers changed for the better or not. That story is yet to be written.

Same with us. The story of your life is not over. The story of my life. There is a reason the rich man remains nameless in this story. Because the rich man is us.

Furthermore, the story of Lazarus and the rich man is not over from the perspective of Christ’s resurrection. In the story, Abraham speaks “as if” someone rises from the dead (Luke 16:31). But someone later did! Jesus overcame the chasm separating this life from the next. Jesus overcame death and grave and opened to all people the way of everlasting life.

This past summer I’ve also watched more movies than I usually do. In the film, “The Gorge” (Apple Original Films, 2025), Cold War soldiers have kept watch over a mysterious and deep canyon since the end of the Second World War. The bottom of this gorge is shrouded in mist.

Decades after decades highly trained soldiers took turns alone at the watch towers on either side, but no one ever spoke nor communicated in any way with their counterpart. The two soldiers, from opposites sides of an impossible divide whom we meet in this film, finally do cross over, literally and figuratively. And what finally breached the divide was love. It’s a love story.

In a pivotal scene the deadly creatures climbed up from the bottom of the gorge and began to attack one of the outposts at the top. The soldier from the other side fired a grappling hook, so he could zip-line across to help defend the other from their common foe. He was motivated by self-giving love which put him at great, personal risk.

Jesus’ resurrection means that eternity starts now. The bridge over the chasm separating this life from the next is already built. God’s love for us breaches this deep and wide chasm that separates us from God and from one another. We who journey in the way of Christ always have a chance to grow, to change, to be transformed into the likeness of Jesus. Because the God of love is a God of second chances.

Even though we may stumble from time to time doing the right thing, even though we, like the rich man, fail to see the need of Lazarus at our gate time and time again (Malina, 2016), we don’t stop trying. Because Jesus’ resurrection lives in us.

The chasm can be breached, with Love as our guide. That is our hope.

References:

Derrickson, S. (Director). (2025). The gorge [Film]. Apple Original Films.

Doyle, B. (2014). The Plover. Picador.

Malina, M. (2016). Mirage gates [Blog]. WordPress. https://raspberryman.ca/2016/09/23/mirage-gates/