It’s all about change today. In the church year, the Transfiguration of Our Lord Sunday not only pivots us from the Christmas cycle of Advent, Christmas and Epiphany to the Resurrection cycle of Lent, Holy Week, and Easter. The Transfiguration is also an event in the life of Jesus wherein he claims his full divinity without denying his full humanity.

First, Jesus’ appearance changes on the mountaintop (Luke 9:28-43a). His face and clothes become dazzling white. And, the voice from the cloud declares Jesus God’s chosen son. Divine.

But the changes don’t stop there. The story doesn’t end with the disciples’ awe and silence atop the mountain in the cloud. There is a purpose for those mountaintop experiences. The purpose is to live on the earth.

Jesus must continue his ministry, his mission to the cross. Alongside his divinity Jesus has to continue to grapple with his humanity. He has to come down, descend to earth, so to speak, and deal with real people. And he is frustrated and angered when he encounters the people, calling them a “perverse generation”. Yes, this Gospel text about the Transfiguration of Our Lord reveals Jesus’ humanity as much as it does his divinity.

Yet, in both the divine and human Jesus, the glory, the presence and greatness of God is witnessed. “All were astounded at the greatness of the Lord,” concludes the Gospel (Luke 6:28-43a).

But the changes don’t stop there! There are others in this story that experience growth, deeper connection and maturity in faith – the healed boy to say the least, the crowds who witness the miracle, as well as the three disciples who were privileged to accompany Jesus to the mountaintop. They were all impacted in different ways. This event changed them.

This event is a key turning point in the disciples’ awareness and experience of their friend and their Lord. They are growing and changing in their faith. From simple fishermen to martyrs – many of them – there is a long narrative in between. And the transfiguration story is an important milestone in that journey towards growth and maturity.

Yes, today is all about change. The disciples in Jesus’ day represent the church today. We are the body of Christ, together. How does a community of people change, never mind individuals? In our hyper individualized society, we don’t pay enough attention to the changes we undergo as a community of faith.

After the Second World War, Sweden was the only country in continental Europe whose citizens drove on the left side of the road. This caused chaos at border crossings and many head-on collisions. So, on September 3, 1967, citizens in Sweden changed from driving on the left side of the road to the right. They called it, “turn around day”.

Because of opposition to this proposed change, a four-year education program was started four years before September 3, 1967, upon the advice of psychologists, so that at 4:50 a.m., “turn around day” began with all traffic halting for 10 minutes. After the 10 minutes were up, at 5:00 a.m. on September 3, 1967, then everyone changed lanes from driving on the left side to the right side of the roads (Watson & Watson, 2025).

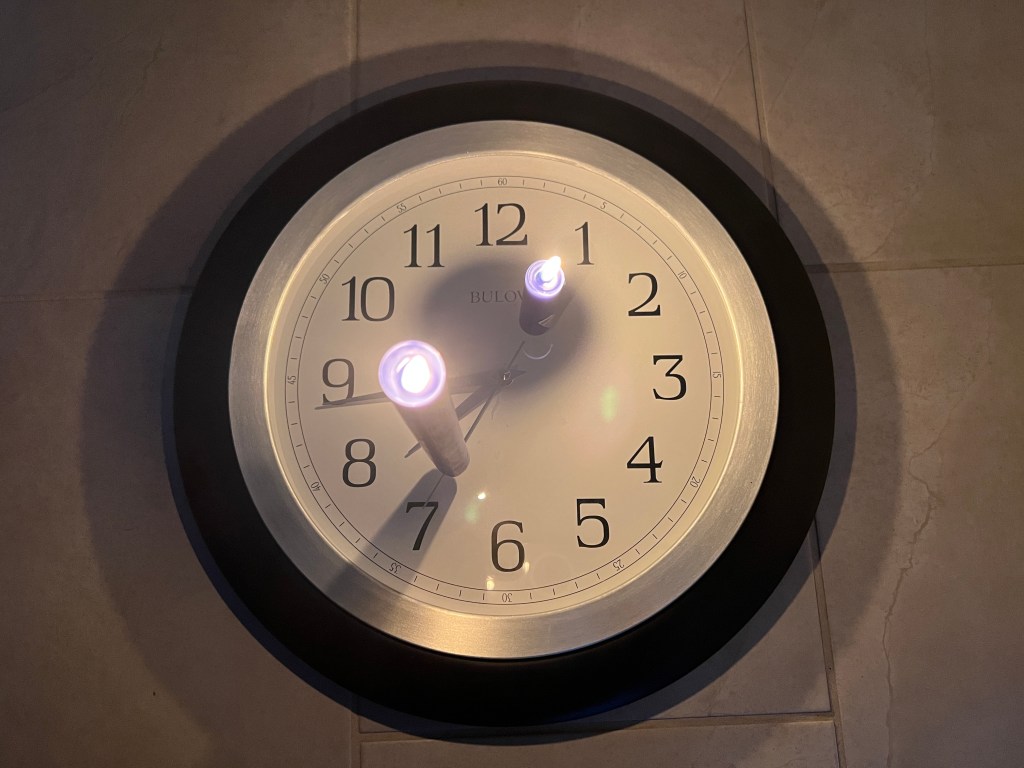

To make their change, the Swedes had to first stop what they had been doing. Psychologists today call it “thought stopping” (Erford, 2020). On the road to recovery and healing, the idea is that one must begin by consciously arresting/stopping the unhelpful automatic thought before substituting an alternative thought, and behaviour.

But long before cognitive behavioural therapists started using this technique, Christian contemplatives were practising a version of thought-stopping in order to make room in their awareness of God. And what they noticed when they stopped everything, including their incessant thinking and activity trying to solve all their problems, what they discovered was that God was already working the desired change in their lives.

The practice was called Statio, the practice of stopping one thing before beginning another. I like to call it a “holy pause”. It is the acknowledgement that in the holy pause is a space of transition and threshold into a sacred dimension. And this holy pause is full of possibility. This place between is a place of stillness, where we let go of what came before and prepare ourselves to enter fully into whatever comes next (Paintner, 2018).

Statio calls us to a sense of reverence for the “fertile spaces” in between all our work and activity “where we can pause and center ourselves and listen” (Paintner, 2018, pp. 8-9). We open up a space within us to receive Christ’s invitation and Spirit to follow the way of Christ, inviting us on the path to healing.

Jesus taught the disciples the importance of a holy pause, on this path of life. The Transfiguration story began in prayer. “They went up a mountain to pray.” That is the way we travel this journey with Jesus. Prayer. In holy pausing, we begin to see God being revealed to us all the time, all around us.

The disciples, you will note, were both elated and terrified. Because those holy pauses aren’t always easy nor are they always immediately gratifying.

The turn-around-day in Sweden was not a popular move, at first. Allegedly some 80% of the population opposed the idea of changing lanes. Maybe because people knew the cost. Whole infrastructures had to be rebuilt and retooled – imagine the cost – signs, intersections, car lights – never mind getting used to driving on the other side of the road (Savage, 2018).

Was it worth it? Car accident insurance claims and more importantly fatal head-on collisions dropped sharply in the months and years following “turn around day”. So, the public effort and expense resulted in saving lives.

And that’s where this Gospel today leads us to and ends with: healing. The cross leads to the empty tomb. That’s the story of the Gospel. Transfiguration – and all those holy pause moments – eventually lead us, in the way of Christ, to resurrection and new life. That is our hope.

References:

Erford, B. T. (2020). 45 techniques every counsellor should know (3rd ed.). Pearson Merrill.

Savage, M. (2018, April 17). A thrilling mission to get the Swedish to change overnight. BBC [website]. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20180417-a-thrilling-mission-to-get-the-swedish-to-change-overnight

Valters Paintner, C. (2018). The soul’s slow ripening. Sorin Books.

Watson, C., & Watson, G. (2025, January 21). Right day. Eternity for Today. Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada. www.eft.elcic.ca