In the last couple weeks, we have worn our poppies and have been challenged to remember.

There is little to question about what actually happened in the First, Great War, the Korean War, The Second World War and all the military conflicts in the last century including Afghanistan. We have the numbers, the maps, the results, the casualties. We honour the soldiers and veterans who made sacrifices in service to their country. We recall the horrors of war and pledge to be agents for peace in the world.

Remembering is important to do. How we remember and what we remember is another question worth pondering.

In recent years whenever my twin brother and I have gotten together we are intentional to remember times especially with my Father, growing up, travelling, spending ordinary days doing ordinary things. As with any life, there are lots of stories to remember.

And what is almost always the case, is that David remembers one aspect of the same event that I don’t; and, I remember a completely different part of that event – which David doesn’t. For example, David remembers the imaginative story Dad told us when we were about ten years old about Mr. Black fighting Mr. White. While he remembers more the content of the story, I remember that when Dad told us that story we were sitting on the back porch after having gone for a bike ride together.

We spend these times reminiscing by ‘filling in’ each other’s gaps in memory. Same event. Just different things remembered. And different things forgotten or overlooked.

In this 500th anniversary year of the Reformation, the Lutheran and Roman Catholic churches have attempted a different tact from the way we have ‘celebrated’ Reformation anniversaries in the past. Listen to what the Lutheran World Federation scholars and Roman Catholic leadership wrote together recently about the task of how we remember the Reformation events of the sixteenth century:

“What happened in the past cannot be changed, but what is remembered of the past and how it is remembered can, with the passage of time, indeed change. Remembrance makes the past present. While the past itself is unalterable, the presence of the past in the present is alterable. In view of 2017 [the 500th anniversary of the start of the Reformation] the point is not to tell a different history, but to tell that history differently.”[1]

That same history, you will know, was used for centuries to incite conflict and division between our churches. Reformation was traditionally a time to celebrate how good we are and how bad they are. Today, in a changed context reflecting globalization, ecumenism and a pile of new research and study about Martin Luther, his times and his theology — these have yielded fresh approaches that emphasize unity rather than division.

Perspectives have changed. And continue to change.

This year in Canada we are also celebrating our 150 years of history with more of a critical eye. We acknowledge publicly, perhaps in a new way, the fact that Canada was already occupied by people long before the first Europeans settled here. This understanding may be challenging for us settlers because for so long we have reaped the vast material benefits of settling and working here.

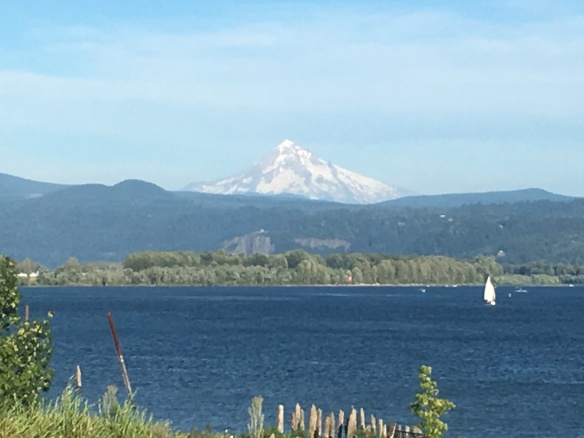

Part of my sabbatical journey took me to Lisbon, Portugal. On the far westernmost coast of continental Europe, Lisbon was a natural launching point for the various expeditions and voyages made by Europeans during the “Age of Discovery”.

On Lisbon’s extensive waterfront at least a couple of impressive monuments stand in celebration of the achievements of European explorers and aviators. There is the looming Monument of Discovery which depicts the personalities of various explorers making their way across the ocean.

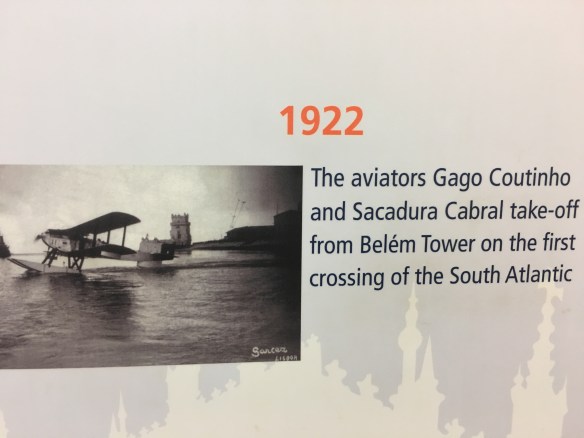

And there is an airplane monument commemorating the historic first south Atlantic crossing in 1922 flown by Gago Coutinho and Sacadura Cabral.

In the decade following Coutinho’s and Cabral’s inaugural south Atlantic flight, another adventuring aviator, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry who is perhaps most well-known for writing the children’s book “The Little Prince”, reflected on what flying did to our understanding of the land upon which we live:

The airplane, he writes, “has revealed to us the true face of the earth. Through all the centuries, in truth, the roads have deceived us … They avoid barren lands, great rocks and sands, they are wedded to the needs of men and go from spring to spring …But our perspective has sharpened, and we have taken a cruel step forward. Flight has brought us knowledge of the straight line. The moment we are airborne we leave behind those [winding] roads … It is only then, from high on our rectilinear course, that we discover the essential bedrock, the stratum of stone and sand and salt…

“Thus do we now assess man on a cosmic scale, observing him through our cabin windows as if through scientific instruments. Thus we are reading our history anew.”[2]

As we retell our history, as we seek understanding of what and how it happened, do we take the winding road, or do we take to the skies?

Amos the reformer was a prophet in ancient Israel. He challenged especially the northern kingdom in the eighth century B.C.E. to accept a new way of worshipping God. No longer where they to worship at the old shrines established by earlier prophets Samuel, Elijah, and Elisha at Beer-sheba, Bethel and Gilgal. Now, they would have to learn to worship God in a central location, at the temple in Jerusalem.[3]

In order to persuade them, he railed against the rituals and heartless pomp often associated with worship in that day.[4] The Israelites’ understanding of their own history needed changing. Without denying or changing the history itself, Amos helped them grow into an appreciation of the centralized worship which was not inconsistent with the Hebrew faith, a faith that had always emphasized care for the poor, the widow, the destitute. As such, Amos was “an agent of reformation”[5].

Whether we speak of ancient Israel, or the Reformation, or the Age of Discovery, or World War Two, or present day Canada, our remembrance is being reformed.

This first week of November is Treaties Recognition Week in Ontario. Listen to what perspective is offered in the writing of our history. Again, this perspective is not untrue. It simply offers a fuller understanding of what happened when Europeans ‘discovered’ this land:

“This native land was the home of many peoples, who have lived here for centuries and millennia. There is extensive archaeological evidence to confirm this statement. North America was occupied long before European strangers from across the ocean ‘got lost’ on their way to India and ignorantly named the inhabitants ‘Indians’.

“The residents of this new land had a deep regard for the practice of hospitality. So they welcomed the strangers to come ashore and opened their lives to these ‘lost’ explorers. This invitation to step out onto the land conveyed a message that did not make sense to the newly-arrived who had their own primary interests; wealth and resources.

“These alien visitors were nominally Christian. They were supported by ‘Christian’ interests intermingled with commercial and imperial motives. The biblical foundations and the practice of hospitality had been lost or buried under the exercise of abusive power that appears to be the inevitable companion of empires seeking to expand their influence and control. Equally forgotten or ignored was the fundamental biblical concept of covenant whose goal is establishing and nurturing respectful relationships that honour the Creator.

“These European strangers had been told by their highest authorities that any people unlike themselves actually were nobodies. The Doctrine of Discovery … reminded the newly-arriving aliens that they were superior to the ‘nobodies’ greeting them in hospitality. The rest is history and now we are trying to ‘get it right’ so that we can discover what it means to live in peace and mutual respect. It is time to set aside suspicion and abuse so that we can again become hospitable to one another as well as to contemporary visitors.”[6]

This anniversary year we sing “O Canada” and this Remembrance Day we’ve worn our poppies. It is important that we remember. It is important that we commemorate our history, good and bad.

How we remember is important, too. What aspects of our remembrance we emphasize speak loudly about the kind of people we are and aspire to be.

Amos presented a pretty bleak picture of Israel’s plight in the eighth century B.C.E. The tone of his message is harsh, doom-and-gloom. It seems the Israelites can do nothing to avoid the inevitable calamity that awaits. It’s easy to lose hope and despair in the present circumstances. It doesn’t look good, what with all that’s going on in the world today.

From the perspective of history, though, we know how the story ends for them. We know the people of God are headed to the trials of Babylonian exile a couple of centuries later. We also know that one day, they do return to Jerusalem to restore the temple worship and re-build their lives at home.

Antoine Saint-Exupéry tells the story of when he and his friends from northern Europe invited some north Africans from the Sahara to visit with them in France.[7] These Bedouin, up until this point in their lives, never left the desert; they only knew the scarcity of water that defined so much of their lives and perspective.

When they climbed in the foothills of the French Alps they came across a thunderous waterfall. The French explained to their astounded friends that this water was enhanced by the Spring run-off of melting snows high above them. After minutes of silence during which the Africans stood transfixed before the bounteous and gorged scene before them, the Europeans turned to continue on their mountain path.

But the Africans didn’t move.

“What are you waiting for?” Saint- Exupéry called back.

“The end. We are waiting for the water to stop running. A stream of water always runs out. We are just curious to see how long it takes.”

They would be waiting there a long time. The prophet Amos concludes his diatribe by doing what so many other prophets of Israel do: They call on the people to have faith in God’s action in the world, God’s righteousness and justice. “Let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.”[8]

God’s justice never runs out. The waters of God’s grace, mercy and truth never cease flowing. Our perspectives, our experience, our opinions are limited and sometimes scarce, if we rely on these alone.

But God’s work continues to gush forth in and all around us. Let us trust and have faith in the never-ending flow of God’s love and presence in the world today. So we may grow into the fullness of God’s vision for us all.

[1] “From Conflict to Communion: Lutheran-Catholic Common Commemoration of the Reformation in 2017” (Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt/Paderborn: Bonifatius, 2013), p.16

[2] Antoine Saint-Exupéry, “Wind, Sand and Stars” trans. by William Rees (New York: Penguin Classics, 2000), p.33-34.

[3] Wil Gafney in David L. Bartlett & Barbara Brown Taylor, eds., “Feasting on the Word: Preaching the Revised Common Lectionary Year A Volume 4” (Kentucky: WJK Press, 2011), p.266-270

[4] Amos 5:18-24

[5] Wil Gafney, ibid., p.268

[6] Reconciling Circle: reconcilingcircle@execulink.com, Daily Readings for Treaties Recognition Week: 5-11 November 2017, Day 1 “Have You Ever”

[7] I summarize and paraphrase his telling from “Wind, Sand and Stars”, ibid., p.54-55

[8] Amos 5:24