A few weeks before Christmas, little Benjamin was thinking about what he really wanted for Christmas. This year, it was a Star Wars Lego set. All his friends had this, and he really wanted one.

And Benjamin wanted to write a letter to Jesus for this gift. His mother said he should really be writing a letter to Santa, but no, Benjamin was serious. Better Jesus; he thought, better chance he’d get this gift by communicating directly to Jesus instead of Santa.

So, Benjamin starts writing: “Dear Jesus, I’ve been a very good kid, and …”

He stops. No, Jesus won’t believe that.

He crumples up the paper, throws it away, and starts again: “Dear Jesus, most of the time, I’ve been a good kid…” He stops again. No, Jesus isn’t going to buy this.

He starts again: “Dear Jesus, I’ve thought about being good…” He thinks a bit, then decides he didn’t like that one either. Benjamin throws on his jacket and heads outside, frustrated and upset.

He walks to the church around the corner. In front of it is set up a large manger scene. And he has a brilliant idea: He grabs the wooden figurine of Mary in his arms and rushes home with it!

He wraps the sculpture in blankets and stuffs it under his bed, then heads over to his desk and starts writing a new letter: “Dear Jesus, if you ever want to see your mother again, send me that Lego set! Your friend, Benjamin.”

At least Benjamin was honest. Before God in all our vulnerability, as the light of God’s gaze rests on us, we may feel inadequate and not good enough. We, then, will stay stuck in negative self-talk and complacent in-action. “How could God use me?” “Not only a sinner but quite unexceptional. Doesn’t God see all the dirt in my life, all the dark corners that even I don’t want to look at?” “Not me!”

“Behold, your servant.”[1]Mary’s first words after hearing the angel’s call for her to bear God’s Son. The New Revised Standard Version replaced the older English “Behold” with the phrase, “Here I am”. Of course, “Here I am”, based on Mary’s initial response to the angel as a precursor to her Song of Praise[2], is now a popular song in our worship book. “Here I Am, Lord.[3]

Interesting that Mary begins her prayerful response to God simply by acknowledging God’s astonishing choice of her: a common, teenager with no pedigree, status or exceptionality to her name. “Behold, your servant.” Yes, God sees her. God favors her. God beholds whom God created, in Mary.

“Behold, your servant” is a statement of profound love. Mary’s very being is seen by God. The light of God’s love shines upon her common, fragile, vulnerable nature. Yes. But the dirt doesn’t matter to God. She is deemed a worthy recipient of God’s good intent and purpose.

As God first beholds Mary, we see in her what is true about God’s relationship to us. As God be-holds, Mary holds the Christ child within her. As God be-holds us with unconditional acceptance and love for who we are, so we hold the presence of the living Lord within us. Not only are we called to receive Jesus, we are called to conceive Jesus in our lives.

A truly remarkable message at Christmas, every year! We become Christ-bearers, to give birth to Jesus’ life and love for this world through how God has uniquely created each one of us–through our words, eyes, hands and heart.[4] We need to be reminded of this truth often.

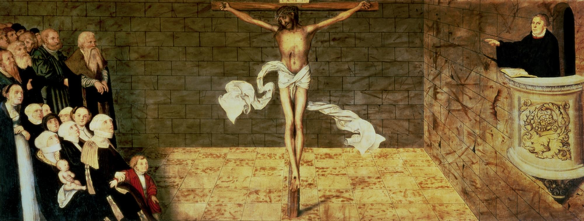

A pre-Reformation era tradition in Germany has recently gained more popularity: It is a ritual that has been practiced mostly in small towns, villages, and rural areas. What happens before Christmas is that each family brings a small statue of Mary to a neighbouring family, where that statue remains in a central location in the household until Christmas day.[5]

This ritual reminds everyone who participates a few important truths: First, your neighbour gives you a statue; you don’t get one for yourself. This part of the ritual is meant to convey that before we say or do anything in response to God, we must acknowledge, as Mary did, that God’s gift first comes to us. Jesus himself later told his disciples a lesson in love: “You did not choose me, but I chose you.”[6]

And secondly, perhaps more importantly, the statue is a visual reminder that each of us is Mary, preparing a place in our own hearts for the presence of Jesus in the Holy Spirit.

You see, when Mary was pregnant with Jesus in that small place within her where the light of the world was gestating and growing – there was a pure heart. Yes, Mary was sinful as any human being. But within her, too, was a holy place where sin had no power, where she reflected the image of God.

Is that not so, with us, too? Each one of us holds the capacity, within ourselves, to carry the presence of the living God in Jesus. What difference would that conviction make in, not only appreciating the place in our own lives where God’s Spirit indwells, but in others?

The statue of Mary in these households reminds families, that despite all the conflict, stress, misunderstandings and sin so obvious in every kind of family, especially at this time of year, we can also look for a place of peace, stillness, and true joy amongst and within our very selves.

We are, at Christmas, reminded by this holy birth and through those familiar biblical characters like Mary, that we can see one another now with what Saint Paul calls the strength of our inner nature, or being.[7]

We can regard one another, though we are different and unique, with a knowledge and belief that each of us holds a space and a place within that is being renewed, transformed and united in God.

Someone once said that to be of help to anyone, you must first be able to see the good, however small, in that person.[8] Then, and only then, can you be effective and genuine in your caregiving. Can we see, first, the good in others? Can we practice doing so this Christmas?

We can be strengthened in this course, nourished at the Table and emboldened in faith to know that God, before anything, “beholds” us in God’s loving gaze, just as we are. God sees the preciousness in each of our lives before dealing with the dirt, and loves us anyway.

So rather than right away assume the worst in us and others, and then like little Benjamin act out on that vision; rather than initially write off others who annoy us because they are different—those strangers and people we don’t understand and maybe even fear …

Perhaps we need Mary to remind us again of her response to God’s beholding of each of us. Perhaps we need to appreciate anew the gift in others that may not on the surface of things be always apparent.

Perhaps God is coming to us again this Christmas, in the guise of a stranger yet one who is truly a lover – one who comes because “God so loved the world”.[9]

Indeed, love is coming. Alleluia! Thanks be to God! Amen!

[1]Luke 1:38

[2]The Magnificat, Luke 1:46-55

[3]“Here I Am Lord”, Daniel L. Schutte (Fortress Press: Evangelical Lutheran Worship, 2006), #574.

[4] Curtis Almquist, Society of Saint John the Evangelist (SSJE) “Brother-Give Us A Word” (22 December 2018), http://www.ssje.org

[5]For more information about the tradition of ‘carrying Mary’ at Christmas, please read Anselm Gruen, “Weihnachten — Einen neuen Anfang” (Verlag Herder Freiburg, 1999), p.39-41

[6]John 15:12-17

[7]2 Corinthians 4:16-18; Ephesians 3:16-19

[8] Yuval Lapide: “Bis du nicht das Gute in einem Menschen siehst, bist du unfähig, ihm zu helfen.“

[9] John 3:16