This text represents a draft of a talk I gave at the Essential Teachings Weekend (ETW) for the Canadian Community for Christian Meditation (wccm-canada.ca) in Alexandria, Ontario (September 21-23, 2018). This was the third of three talks, entitled “Stages of the Journey” which complemented the first talk (“The Essential Teaching”), and the second talk (“History of the Tradition”).

STAGES OF THE JOURNEY

The notion of journey, or pilgrimage, originates in the very birth of Christianity. Christ-followers came to be known as “Christian” only after Christianity became the official religion of the empire in the fourth century C.E. But until then they were known as those who followed in the “Way”, implying a path, a road, a journey to be followed.[1]

The notion of motion is integral to those who try to follow Jesus to this day. In the last several decades the pilgrimage has become very popular, especially the Camino de Santiago which attracts hundreds of thousands of pilgrims every year. Many who walk the eight-hundred-kilometre journey across the Iberian Peninsula in northern Spain will attest that the journey is a metaphor for the passage of life or traversing some interior path.

Indeed, the exterior journey, such as the Camino, mirrors the internal journey where one explores the contours of the heart and the landscape of the soul. It is a journey that takes time and is fraught with danger. And, at some level, determination, dedication and faithfulness.

Speaking of Spain, it was perhaps the great Spanish mystics of the sixteenth century – Theresa of Avila and St John of the Cross – who first in their writings exemplified the interior and often difficult journeys of faith, such as in ‘The Dark Night of the Soul’. Recently, Richard Rohr describes it best when he asserts that it is through great suffering or great love by which we move along the path towards meaningful change and growth. Crises of faith and challenging circumstances of life are invitations to go deeper into the truth of self and the presence of God.

I want to describe these two journeys to you by using several metaphors—involving water, an hourglass, a wagon wheel and the Exodus story from the Bible describing the desert wanderings of a people. These symbols and images I hope will convey effectively the meaning of these journeys.

When we commit to meditation, we are undertaking what I would summarize as two journeys, operating on a couple of levels.

1.THE FIRST JOURNEY

The first is journey that happens during the time of the meditation.

The Ottawa river at Petawawa Point: the rough & the smooth

I used to live close to Petawawa Point in the Upper Ottawa Valley. Petawawa Point was a lovely spot on the Ottawa River which broadened out into a large lake dotted by several islands. And, I loved to kayak through and around these islands and waterways.

When I first put out onto the river at the beach I was immediately into the main channel lined by the green and red marker buoys, where all the motor boats would roar through. This was the turbulent section of my paddle. I often fought the waves created in the wake of speeding, noisy boats. This part demanded my determination, resolve, and good intention to get past the hurly-burly and through the narrow passage between a couple of islands.

Once through, the water opened up into an area of the river where the large, loud motor boats avoided – only the loons, hawks and sometimes eagles. Here was the more peaceful part of my paddling experience, one that I have treasured to this day.

Meditators have often mentioned to me—and I have experienced this too—that during the first fifteen to twenty minutes they are fighting themselves, their thoughts and distractions. And then something inexplicable happens, and they finally get into some kind of peaceful rhythm with their mantra in the last five minutes! Whether it takes you fifteen minutes, or only a couple of minutes into the meditation, it’s important to keep paddling even when things settle down in your brain.

You see, the temptation once I got through the busy channel into the peaceful expanse of the river was to stop paddling altogether and just float for a while. I would gaze at the birds flying, the clouds in the sky and the distant Laurentian Hills. It was beautiful!

In meditation, this is called the “pernicious peace”, where we just float in some kind of relaxed state our mind really doing nothing and it just feels good and we don’t want to do anything else. I soon realized however I wasn’t doing what I had set out to do. I came to the river to paddle, not to float. And as soon as I dipped my paddle again in the peaceful river, I found my stride, purpose and joy.

When we begin in our meditation, we usually immediately encounter the distractions of the mind. For example, I ruminate over what I am I having for supper, what groceries I need to pick up, what errands I need to run, how will I handle a problem at work or in my family, where am I going on my vacation, the main point of my upcoming sermon, etc.

How do we respond to these distractions? Do we simply float in some sleepy, dream-world, following the course of this stream-of-consciousness? Yes, sometimes we do fall asleep during meditation. It’s good to be relaxed. Yet, we also pay attention and are alert to the experience by remaining faithful to the paddle, so to speak, to the mantra. We focus the mind.

On the underwater rock: dealing with distractions

Another water image, from Thomas Keating, may help us.[2]It is the example of sitting on a large rock on the bottom of the river. Here, deep under the water you watch far above you the boats of various sizes and shapes float by and down the river. These boats represent all our thoughts and distractions. Often, the temptation of our mind is too great, and we push ourselves off the rock—it’s so easy! —and we swim to the surface.

Sometimes, we will even climb into the boats and sail on down the river in these thoughts. In other words, we will let our minds sink into thinking about it for some time in our meditation. Of course, when we do this, we are not saying our mantra, which is the discipline and faithfulness of sitting on that rock down below.

It’s important not to be harsh with yourself on this journey. Give permission for the boats to come by your mind in this river. Then, as you return to the word, you let these distractions keep floating on down the river. Let them go. Return to the place of deep silence, stillness, on the rock deep below.

Despite the incessant distractions of the mind that come to me during my meditation, I continue to ‘return to the Lord’ and my mantra. Someone once said that it is ok to ‘catch yourself’ in a distraction during meditation. In fact, the more often you catch yourself and gently return to the mantra, the better. Why? Because each time you return to the word, it’s one more time you are loving God. Each time I bring my concentration to the saying of the word, I am offering my love to Jesus. Each time I say the word, I am saying, “I love you” to Jesus.

The journey throughout the meditation period may appear simple. We sit quietly and in stillness for twenty minutes not doing anything except saying, interiorly, the mantra. But it is not easy. We confront in this journey the imprinting of our go-go culture and a hyper-active environment upon our egos. We encounter our very humanity in this journey —

A humanity which incessantly strives to accumulate more information and judge progress according to expectations. We already go into it expecting it gets easier over time. We expect benefits to accrue, like lower blood pressure and more patience. And when nothing like this happens after meditating for a few months or years, we give up. This is a spiritual capitalism.

We encounter our very humanity which also craves stimulation and distraction. Already in 1985, Neil Postman wrote a book indicting our culture with the provocative title: “Amusing ourselves to Death”. For most of our daily lives we choose to keep busy or entertain ourselves rather than sit still and face the truth of ourselves. No wonder we are bothered by distraction during meditation.

We encounter our very humanity which finds self-worth in active productivity. We do therefore we are – the mantra of our culture. The more we produce, the more we have to show for in our day, in our vocations, the better we are. So, it just doesn’t make sense from this perspective to be so unproductive by sitting still and doing nothing with ourselves, really. What’s to show for, after twenty minutes of idleness?

And so, we may also, at deeper levels, encounter anxiety, fear and/or anger – which represent our resistance to the journey of our meditation. These normal, human feelings, given now the freedom of space, time and a loosened ego, erupt to the point of a significant disruption.

When I first started on this journey in 2004, I was beset by anxiety, to the point where I felt that I might explode during the silence and the stillness, to the point where I felt I would run screaming from the meditation room. The waves in that channel from the wake of the speeding motor boats threatened to swamp and drown me! I remember how I resisted the letting go, by asking for example that I not sit in the circle but by the wall in a corner of the room. And then, by suggesting we should sit wherever we want to, not necessarily in a circle. Anything to assert my control, even over the meditation period.

Here, depending on the nature of the deep-seeded emotional pain, you may want to encourage those who find meditation times a time of suffering to seek help to deal with whatever is being uncovered—loosened—during meditation. Some have expressed concern that when we open up our inner lives in meditation, the devil/evil will come in. Laurence Freeman, to this question, said: “It is more likely the devil will come out! Negative feelings and the forces of the shadow will get released as repression is lifted. This is quite natural although it’s important to be prepared for the inner turbulence it can create at times.”[3]

This becomes a journey, then, of healing and transformation.

2. THE SECOND JOURNEY

This journey of healing, then, links us to the second journey operating at another yet concurrent level. The second journey we undertake when we meditate connects us with our whole life, indeed life’s journey.

Being a meditator is about slowly but surely learning how to meet life’s greatest moments with grace, acceptance, generosity, courage and faith. Meditating teaches us how to navigate a crisis of faith, a crisis in our relationships, in our work and in our health. It is about forming an attitude toward life in general. Meditating trains us to bea prayer rather than merely say prayers from time to time. This is contemplation: an inner attitude to all of life so that we are indeed praying always, or as Saint Paul puts it, to pray without ceasing.[4]

The dropping stone in water: deeper we go & letting it happen

James Finley talks about a dropping stone in the water, a journey characterized by a deeper simplicity, a deeper solitude and a deeper silence. He describes well this image of a descent.

“Imagine,” he writes, the stone is “falling … And the water in which the stone is falling is bottomless. So, it’s falling forever … And the water in which the stone is falling is falling along an underwater cliff. And there are little protrusions along this cliff and every so often, the stone lands on one of these protrusions; and pauses in its descent. And in the movements of the water, it rolls off and it continues on and on and on and on.

“Now imagine you are that stone; and imagine we’re all falling forever into God. And imagine you momentarily land on a little protrusion where you get to a place and where you say, ‘You know what? I think I’ll stop here and set up shop and get my bearings and settle in. After all, this is deep enough. That’s as far as I need and want to go. It’s comfortable here.’

“And then you fall in love, or your mother dies, or you have terminal cancer, or you’re utterly taken by the look in the eyes of one who suffers. And you are dislodged, by [a great love or great suffering], dislodged from the ability to live on your own terms and from the perception that the point you’ve come to is deep enough for you.

“And so, you continue on your descent, experiencing successive dislodging from anything less than the infinite union and infinite love which calls us deeper.”[5]

Meditating teaches us not to give up on this journey to a deeper contemplation. Some of the comments I have heard from parishioners who came only to one or two sessions of meditation. And then they declare as if for all time: “I don’t like it.” “It’s not for me.”

Meditation is emblematic of staying the course with what is important, of giving what is important a chance and committing to the path, the pilgrimage – even though we fall short time and time again. And as John Brierley mentions in his introduction to his popular guide for pilgrims, “We are not human beings on a spiritual journey, we are spiritual beings on a human journey.”[6]A very human journey. We will encounter and deal with all our inner and outer limitations on this journey. Sometimes we will need to stop because the human path challenges us in ways we must address. Sometimes the human path will keep us from embracing the fullness of the journey in what it offers.

The Exodus: a journey of transformation to liberation that never seems to end

The Exodus, from the bible, is a narrative of a desert wandering that takes a long time, much longer than you would think: If only the Israelites under Moses’ leadership walked a straight line from start to finish!

The journey, however, is much more than you think. After escaping the shackles, confines and suffering of slavery in Egypt, the Israelites are now a free people, or so you would think. Liberation as the goal is however a process that involves transformation. They are free to go to the Promised Land, yes. And yet, their journey in the desert, confronting the fierce landscape of their souls, is rife with resistance and conflict as they take a long and circuitous route towards their liberation.

They complain to Moses. They say they would rather return to the fleshpots of Egypt than eat the Manna from heaven given in the desert. They create distractions and build a golden calf. It’s not an easy journey for them, to get to the Promised Land. It’s not easy, to be free.

Yet, as what happens on the first journey (during a meditation period by returning to our mantra), we return to the Lord our God over and over on the journey of life. We learn over time to trust the journey and stay the course. By being committed to the journey of meditation, we cultivate the spiritual muscle of trust, despite the resistance and conflict we confront within us.

Trusting in God. Trusting in life. Trusting that the trajectory of our pilgrimage is heading in the right direction despite all the bumps in the road. As the small stone on the underwater ledge drops to a deeper level through every crisis and twist and turn of life, we learn to surrender and let go. Richard Rohr, I believe it was, said that all great spirituality is about letting go. Of course, trusting this process involves taking the risk as we ‘fall’ deeper into the mystery of life and God towards an unknown yet hopeful future.

Riverbank: dipping into something bigger

On this journey of life we remain faithful to the path, which winds its way on the banks of a great river. The river is moving. We stay connected to the river, regularly stepping into the waters to say our mantra. We step into the flow of the river. The current is strong. The River is the prayer that continues in our hearts that is Jesus’ prayer to Abba.[7]

When we so dip into the prayer of Christ, which is ongoing, we participate in the living consciousness of Jesus who continues to flow in the trinitarian dance of relationship with God. In meditation, we learn that life is not limited to myprayer or ourprayer. Dipping into the river is stepping into a larger field of consciousness. It is dipping into the very prayer of God in which we participate every time we meditate.

If this journey is not about us, we therefore look to relate to one another, especially those who suffer. We see in the other our common humanity and act in ways that are consistent with the grace that first holds us. In the end, meditation’s journeys lead us beyond ourselves, to others in love, and to God in love.

Meditation, therefore, is essentially a journey in community. It’s a pilgrimage we undertake with others and for others. It’s not a solitary journey. Thus, the importance, at least, of attending/being part of a weekly meditation group.

Contemplation, then, leads to action. The journey of life, like the journey through the time of meditation, embraces paradox. While on the surface seeming opposite and incompatible, contemplation and action are integrated into the whole. Both are essential on the Way.

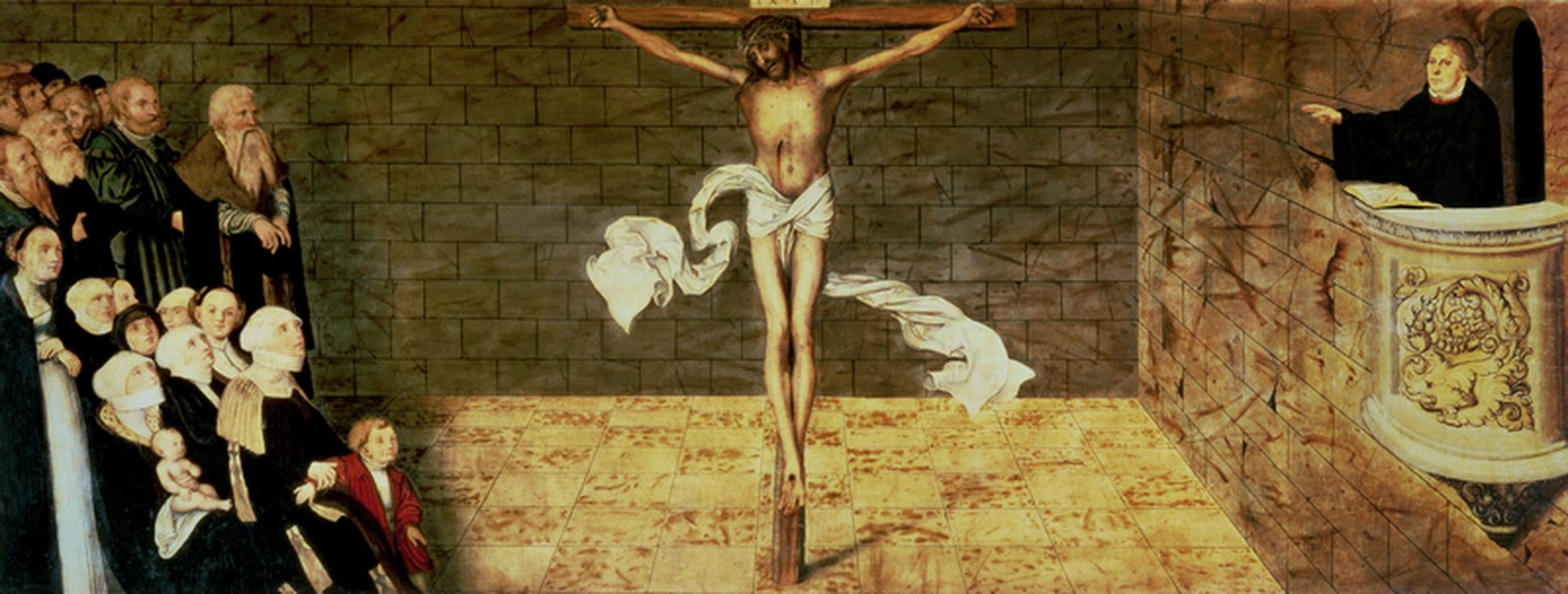

In truth, following Jesus is embracing paradox. “In order to find your life you must lose it,” he says.[8]Later, Paul announces that strength is found in weakness and the weak have shamed the wise.[9]Of course, the major paradox of the faith centres on the Cross; God is defeated. And in that vulnerability and loss, Christ and Christ-followers discover new life and resurrection.[10]

To do well on the journey of contemplation, on the path of meditation and indeed life, is to accept the ambiguities, the ‘greys’ and the uncertainties of the Way. As any peregrino will tell you on the Camino de Santiago, there is no end to the daily surprises and challenges that meet the faithful pilgrim. If one’s mind is already made up about what to expect and how it should go, disappointment and premature abandonment of the journey is likely to follow.

To do well on the journey corresponds to the capacity you have to hold paradox in your heart. The solution finds itself more in the both/and of a challenge rather than an either/or. Perhaps the faithful pilgrim will have to compromise an initial expectation to walk every step of the way. And, in dealing with an unexpected injury, the pilgrim might need to take the train or bus for part of the journey. In other words, the dualistic mind is the enemy of the contemplative path.

On the spectrum between action and contemplation, where do you find yourself? If you want to become a better meditator and enrich your soul, then seek social justice. Become active in the cause of a better humanity and a better creation. Speaking to a group of social activists and community organizers, I would counsel the opposite: If you want to become a better justice-seeker and advocate, then dedicate more of your time to meditation. Both/And.

The hourglass: flow ever deeper

The direction of the flow in an hourglass starts at the top in a basin that collects all, then moves downward into a narrowing, finally coming through into an expansive region flowing ever deeper and wider.

The top of the hourglass represents all that our mind grapples with – the squirrel brain. It represents all our efforts, desires and intentions – good and bad – of a furtive, compulsive ego to come to the expressed need for this practice. “I need some quiet in my life.” “I enjoy the silence shared with others.” “I need to slow down.” “I like being by myself.” Admittedly, many introverts are enticed by the prospect of meditation. Although these are the same people who realize, on the path, it is much more than stoking the flames of a rich imagination or escapist tendencies – all ego-driven.

On the path, then, meditation leads us deeper into the heart, at the narrows. This is the place of a pure heart, a singular, aligned heart-mind place—some have called it the still-point.

From this point, the journey then expands as we go deeper and farther into the broad, ever-expansive areas, towards the infinite depths involving others and participating actively with all creation.

The wagon wheel: towards the still point

Teachers of Christian Meditation, such as Laurence Freeman, have used the image of a wagon wheel to describe how different forms of prayer relate. These various ways of praying – body prayer, labyrinth walking, petitionary, sacramental, song, poetry, art – represent the spokes on the wheel. All of them attach to the centre.

At the centre of the wheel is the hub. And when the wheel is in motion, which it must be in order to fulfill its purpose and continue on the road, the one part of the wheel that remains still and sure is the hub. This is the place of meeting, convergence, the point, the centre: the Jesus consciousness. Always in motion yet always still. The still-point. Another paradox of prayer. Action and Contemplation.

If the hub is vibrating and not still while the wheel is in motion, then the wheel is out of balance and there is something wrong. The whole riggings may even fall apart if not attended to! For the wheel to function properly, the hub must remain still even as the wheel is rotating at high speeds.

It is here at the infinite center, time and time again, where our prayers lead. Like the labyrinth whose destination is the centre, it is on the path to this centre where we experience a taste and a foretaste of the feast to come, where we taste the freedom and joy of the Promised Land, a land flowing with milk and honey. Where we can be free.

Questions for reflection

- Which image presented here about the journey of meditation touches you immediately and speaks to you most effectively?

- On the spectrum between action and contemplation, in which direction do you naturally lean? What are some ways you can improve the balance in your life?

[1]Acts 18:25; 19:9; 19:23; 22:4; 24:22

[2]Cited by Cynthia Bourgeault, transcribed from the recording of a live retreat titled, An Introduction to Centering Prayer given in Auckland, New Zealand, in October 2009 (www.contemplative.org)

[3]Fr. Laurence Freeman, A Pearl of Great Price.

[4]1 Thessalonians 5:17

[5] Adapted from James Finley, Intimacy: The Divine Ambush, disc 6 (Center for Action and Contemplation, 2013); cited in Richard Rohr, Daily Meditation, www.cac.org, April 27,2018

[6]John Brierley, A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Camino de Santiago(Camino Guides, 2017)

[7]In the Garden of Gethsemane on the night before his death, Jesus addressed God in prayer with this Aramaic word, meaning ‘Dad’.

[8]Matthew 10:39

[9]1 Corinthians 1-2

[10]All four Gospels – Matthew, Mark, Luke & John – conclude with lengthy passion narratives.