Jesus commanded that we shall love our neighbour as ourselves (Matthew 22:36-40). This commandment motivates me to participate this afternoon in the clerics’ cycling challenge (www.clericchallenge.com), initiated by Imam Mohamad Jebara.

Practically, then, what Jesus’ commandment means is that if you love someone, you want to know something about her or him. You want to know who she is, what he values, and how they orient their life. If you love someone, you take the time to talk to him, get to know her, and in so doing, you share yourself as well.

Love shows itself in attention to another, in accepting another on their own terms — yes, and in a willingness to learn something new, to think about things in a new way, and to grow together in friendship and harmony.

When I say Christians are called to love their Jewish or Muslim neighbours, for example, I mean we are called to develop relationships of mutual affection, understanding, and appreciation (Kristin Johnston Largen, “Interreligious Learning and Teaching” Fortress Press, 2014, p.59). Then, we love our neighbour as ourselves, thus fulfilling Jesus’ commandment.

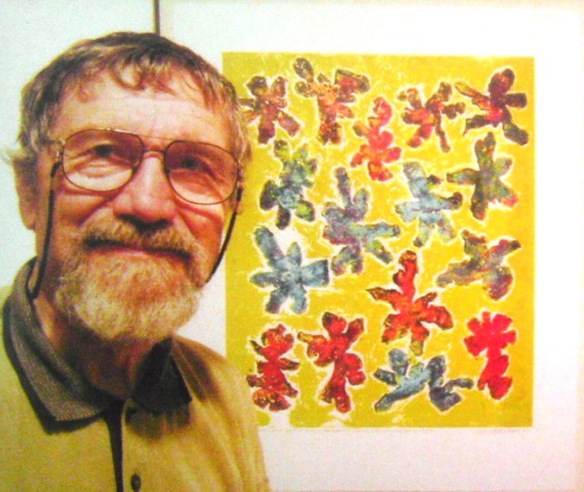

I had the pleasure of viewing some artwork this past week at the Rothwell Gallery on Montreal Road in Ottawa. The Gallery is presenting until October 24th the work of the late Leonard Gerbrandt (1942-2010) who travelled the world and created beautiful impressionistic watercolours and prints especially about the structures of various land and waterscapes. I was given a personal tour by Ute, his spouse, of the hundred pieces or so displayed in the gallery.

When we began the tour, she asked me to guess what colour appears and is prevalent in the vast majority of his art. With a twinkle in her eye, she confessed that this particular colour also happened to be his favourite. And so I went to work. At first, I suggested it was the earth tone greens, even maybe the rust, terracotta and orange/reds. No. No. And no.

As we reflected on one specific piece of art I marvelled how Leonard mixed the blues to distinguish sky and sea. Ute smiled, then said, it was blue indeed. I quickly travelled through the gallery looking anew at the paintings. And you know what? It was true! Now, I could see it — blue indeed found its way into almost all his paintings. Why didn’t I see that at first?

Blue, after all, is my favourite colour too (No political association, though!). And then I pondered further why I couldn’t see what had always been my favourite colour. Had I been distracted by the flashiness of other ‘colours’? Did I take ‘my colour’ for granted? What were ‘the blocks’ inside of me preventing me from seeing what was most important to me? Pride? Anger? Fear? Shame? Greed? Why couldn’t I appreciate fully the beauty that was staring me in the face, for me?

Of course, colours would not exist without the presence of light. In fact, it is how the light is represented in a work of art that brings out the textures and hues created by the paint brush. I also believe that art, like music, serves to reflect back to us an inner state — and that is why art and music can be so powerful conveyors of meaning and truth about ourselves and the world at any given moment in time.

The living Jesus is with us, and in our hearts through the Holy Spirit. The love of God propels the Spirit to move us in the the way of Jesus. And yet, we block our sight. We can’t see the light. What are those blocks that keep us from living out of our nature that is being renewed day by day? What keeps us from loving our neighbour? Is it fear of the unknown? Is it a shame that is deeply imbedded? Is it the fire of anger, the pain of regret, the poison of hatred, the paralysis of mistrust?

“Out of his anguish he shall see light” (Isaiah 53:11)

This phrase comes from a larger so-called suffering servant poem from the prophet Isaiah. Christians have read Jesus Christ into the role of the servant even though the text was originally heard among the people of Israel hundreds of years before Christ. The ‘servant’ could refer to the people as a whole suffering in Babylonian exile, or to a specific individual (i.e. Persian King Cyrus /Isaiah 45) who liberated the Israelites and led them home to Jerusalem.

This exegesis is important and we need to tread carefully in working with sacred texts that we share with our Jewish neighbours. We Christians know the sacrifice of Jesus on the Cross for our liberation, indeed for the whole world. Jesus fits the suffering servant-narrative from Isaiah. Let’s work with this.

The anguish Jesus experiences in his suffering and death reflects a God who is fundamentally relational. And God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit relates to us in our very own humanity. Thanks to Jesus who showed us the way not just in his divinity but especially in his very own humanity. ‘Anguish’ after all, is a human emotion grounded in love. That is, “to anguish over the loss of a loved one” (online dictionary definition).

Not only does Jesus know our suffering in a shared humanity, he feels for us because of God’s intense love for us. The author of Hebrews is therefore able to describe Jesus as the ultimate high priest, who “is able to deal gently with the ignorant and wayward, since he himself is subject to [this] weakness” (5:2). In short, Jesus helps us “see the light” because of God’s deep anguish-filled love for us. God grieves losing us to our sin, and will not stop short in going the distance — even sacrificing his own life — so that we too will see things as they truly are, in the brilliance of God.

In prayer, 14th century Christian mystic Julian of Norwich reflected the divine stance: “I am light and grace which is all blessed love.” May our words and deeds reflect the light of Christ to our neighbours, in all grace and love.