After receiving the visit from the angel Gabriel announcing to her that she would bear the Christ child, Mary came in haste to meet with her cousin and friend, Elizabeth. In the midst of conversations between people – the angel and Mary, then Elizabeth and Mary (Luke 1:39-55) — the word of God comes. The Word doesn’t come outside of a conversation.

I read recently a definition for the Word made flesh as Conversation (Loorz, 2021). Yes, conversation. God speaks existence into being (Genesis 1-2). God creates by issuing forth a word.

But then that Word needs to be received. That word needs a response in order to take root and grow. The Word of God, Jesus Christ, as the Great Conversation, is given and received. The first Christmas didn’t happen without conversation, lovingly given and lovingly received. God spoke Christmas into being.

As they say, the world is black and white until you fall in love. Then you see the world in colour. In her book entitled Love in Colour cataloguing love stories and myths from around the world, Bolu Babalola (2021) wrote, “Love is the prism through which I see the world.”

If we will keep Christ in Christmas then we need to start with love, because “God so loved the world that He gave his only Son” (John 3:16).

Speaking of colours, then, what is your favourite Christmas colour? Red and green likely top the list. Others like white with gold. The classic debate in households is whether to go with multi-coloured lights on the tree or stick with pin-prick white to mimic the stars in the sky. Or, mix them all together? Which do you prefer?

Blue is the colour now used in churches during the season before Christmas, the season called Advent. The colour blue is an interesting choice. Why, blue? At this time of year when the days are short, we hear the colour blue perhaps associated more with our mood – the winter blues.

Some believe blue is the colour of Advent because it represents the colour of the sky at the time of Jesus’ birth (Coman, 2024). The 13th century Italian artist, Giotto, tried to replicate blue in his depiction of the nativity:

https://www.worldhistory.org/image/12682/the-nativity-by-giotto/

We see blue whenever we look up and far into the distance towards the horizon where sea and sky meet. Looking into the distance likely means we are, from the perspective of feet on the ground, looking at a whole lot of blue, pointing us to the limitless expanse of the universe. And so, blue is the colour of hope, yearning and longing.

Yet, here on earth the colour blue is extremely rare in nature. Less than 10% of all plant species are blue and even so, most of the time their blue is an optical illusion.

It’s an optical illusion created by the refraction of light against what is actually red pigment. The only plant with genuinely blue leaves lives on the floor of the rainforest in South America.

But what really stands out is that while all other plant material changes colour when it dies, blue flowers are the only flowers that retain their colour in death. They retain their colour in death – maybe to remind the world that they haven’t gone away, that they have made their mark, that they, in some way we can’t explain or see with our eyes, live on. Blue is then also the colour of steadfastness. From everlasting to everlasting.

In the end, as we still walk by faith on this planet, it really doesn’t matter what colour you prefer. It doesn’t matter whether the Advent candles are all red or all blue, or all purple or some purple and one pink, or all blue and one white or all white.

The important thing is that you know why you are using the colours you are using. What is the story behind the colours you use? And how do those colours reflect a part of the Christmas story surrounding the arrival of God and God’s love to this earth?

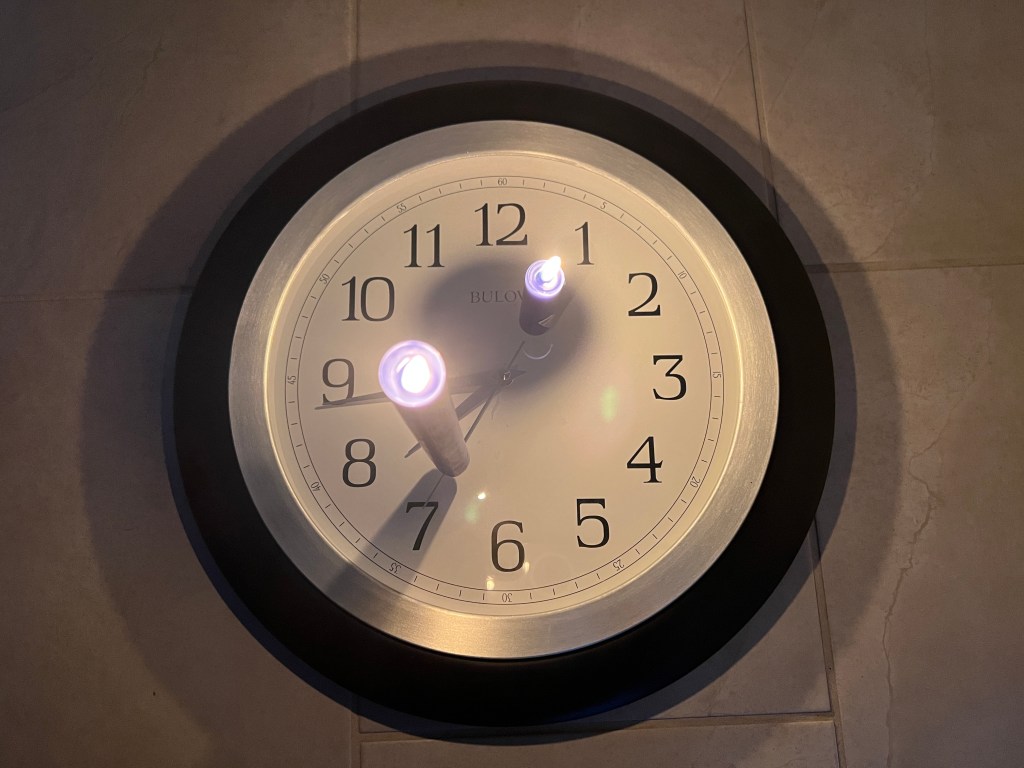

Today we lit the fourth and final candle on the wreath. This fourth candle is called the Love candle. When we know why we do certain things, we can then appreciate why others do it differently. We practice love. What are the reasons they have for the choices and decisions they make – regarding their traditions, their background stories?

We don’t love because others start behaving as we do. Love isn’t about making others conform to our way of doing things. Instead, love is appreciating and being genuinely curious about where the other person is coming from, and letting them know it!

And that’s how we respond in love. That’s how we keep the conversation going. Loving others is behaving in ways and saying things in order to keep the conversation going. The goal at Christmas is to love. The Christmas story lives in us when we keep the conversation going, when we don’t shut it down.

Mary said yes to the angel’s Word from God. Her heart opened even though her mind must have had many questions. Her heart expanded to include the Word of God into her life. She kept the great conversation of God’s love going in her. And her responses in love got the whole ball rolling. And Christmas happened. Thanks be to God!

References:

Babalola, B. (2021). Love in colour: Mythical tales from around the world, retold. William Morrow.

Coman, S. (2024). Seeds of hope: Day 5. Lutherans Connect. https://lcseedsofhope.blogspot.com/2024/12/day-5.html

Loorz, V. (2021). Church of the wild: How nature invites us into the sacred. Broadleaf.