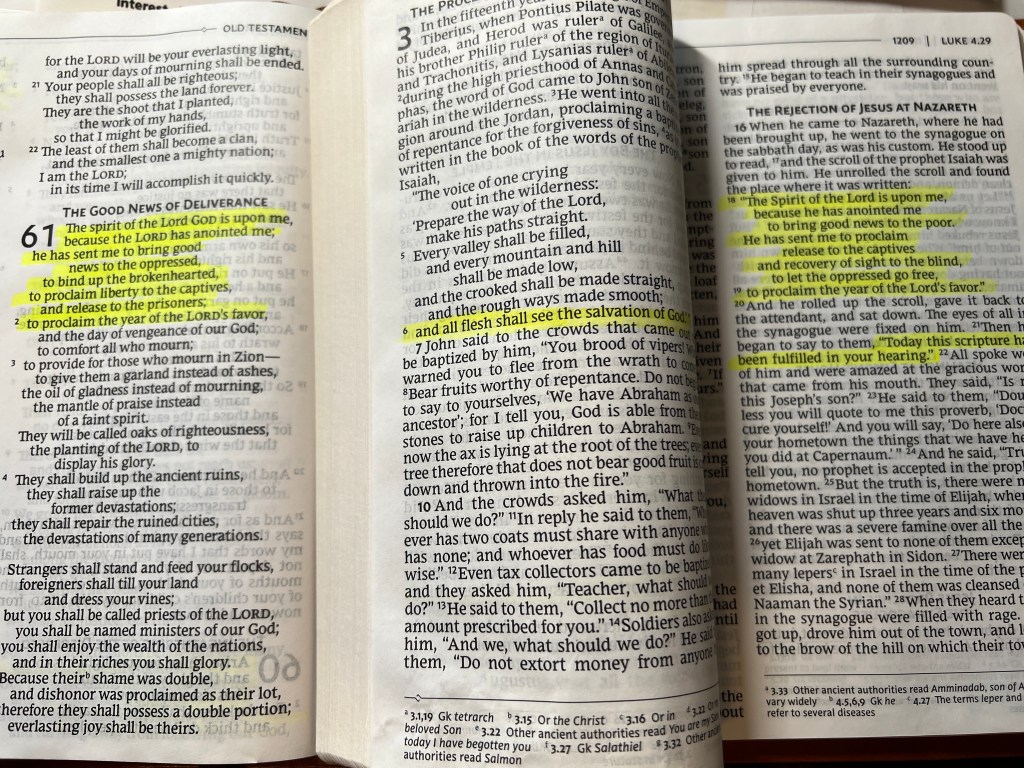

“Love your enemies” (Luke 6:27) is a teaching from Jesus that hits especially hard in today’s economic and political climate. Because loving your opposition is not how you win. Loving your enemies goes against the grain of our conditioning.

Using a hockey analogy, we naturally want to go on the offensive when facing adversity. We want to fight back, tit-for-tat. Seeking revenge is a strong motivator, isn’t it?

But good hockey minds know that focusing only on offense usually means losing the game. Avoiding sound defensive play is not a winning strategy. As they say, defence wins championships.

Winning, in the end, is about nurturing love and care for the battle that goes on in your end of the ice. Loving your enemies is first loving and taking care of your neck of the woods, in your backyard, whenever challenges or personal adversity appear.

So, on the one hand, loving your enemy is NOT about being a doormat and taking abuse. On the other hand, if the aim of any relationship is to always and unquestionably have the upper hand, that is no relationship.

Indeed, the problem with a bulldog approach to the challenges we face is that it more often than not keeps you stuck, by avoiding the things in your own life which you are scared to confront. These are issues that lurk in the places you don’t want to go. Occasions of adversity are invitations and opportunities to first take stock and look in your own life for whatever needs attention there.

Imagine these issues as “gnawing rats” (Loomans cited in Burkeman, 2024). How do you deal with these rats in your life? Impulsively we may want to eradicate and stomp the bad parts out of us, eliminate them completely. With force of willpower we will confront those rats and attack them with brute force and hatred even, eh?

The problem is that this approach simply replaces one kind of hatred (“Stay away from me!”) with another (“I’m going to destroy you!”). And that’s only a recipe for more avoidance over the long term, “because who wants to spend their life fighting rats?” (Burkeman, 2024, p. 62).

“Love your enemies,” says Jesus. What about befriending the rats instead? What about turning towards them and allowing them to exist alongside? There are benefits to this approach. Following Jesus’ command isn’t merely about being mindlessly obedient and doing whatever Jesus says never mind us. Jesus truly had our wellbeing, our healing in mind when he gave us this command. Jesus wants the best for us, wants us to be healthy.

First, to befriend a rat is to defuse the anxiety we feel, because we change the kind of relationship we have with it. We turn that gnawing rat into an acceptable part of our reality. By doing this, we can begin to accept that the situation is real, no matter how fervently we might wish that it weren’t.

But we need to do something that initially feels uncomfortable. What would it take to befriend the gnawing rats in your life? “Loving your enemy” becomes an act requiring real courage – more courage, perhaps, than the standard confrontational approach. “Loving your enemy” becomes like reconciling yourself to reality rather than getting into a bar fight with it.

This is not passivity nor, as I said, is it being a doormat. It’s a pragmatic way, Jesus teaches, to increase our capacity to do something positive while becoming ever more willing to acknowledge that things are as they are, whether we like it or not (Burkeman, 2024).

Last week walking through the thick snow in the uncharacteristically quiet Arnprior Grove, I caught sight of a quick movement at the base of a tree. But it was too quick for me to recognize what it was. Seeing the tiny creature reminded me of an Indigenous tale taught by the late Canadian writer Richard Wagamese, whose story about true power I paraphrase here:

A young man dreamed of being a great warrior. In his mind’s eye he envisioned himself displaying tremendous bravery and earning the love and admiration of his people. The young man knew that the greatest warriors were those who possessed the strongest spirit and wisdom. He longed to become the greatest defender of his people.

And so he approached the Elder of his village. He told the Old One of his dream, of the great love and respect he felt within himself for his people and of his desire to protect them.

He asked the Old One to grant him the power of the most respected animal in all of the animal kingdom. With this power, the young man would be able to become as widely respected as this animal.

The Old One smiled. Although he appreciated the young man’s earnest desire he recognized that this was the time for a great teaching. So he told the young man that he would gladly grant him this power if the youngster could accurately identify the animal who commanded the most respect from his animal brothers and sisters.

The young warrior smiled. It was obvious to him that the grizzly bear commanded the most respect in the animal world. He stated this to the Elder and sat back awaiting the granting of the bear’s power.

The Old One smiled. He told the young man to guess again, for despite the immense courage and ferocity of the grizzly, there was one who commanded greater respect.

One by one, the young man named the animals he felt possessed the adequate amount of fierceness, courage, boldness, and fighting power to earn the awe of his four-legged brothers and sisters. He named the wolverine, the eagle, the cougar, the wolf and the bison, but each time the Old One simply smiled and told him to guess again.

Finally, in confusion the young man surrendered. The Elder told the young man he had guessed as wisely as he could. However, not many knew the most respected of animals because the most respected one is seldom seen and even more seldom mentioned. It is the tiny mole, the Old One said.

The tiny, sightless mole who lives within the earth. Because the mole is constantly in touch with Mother Earth, the mole is able to learn from her every day. Whenever some creature walked across the ground above, the mole could feel the vibration in the earth. In order for the mole to know whether or not it was in danger, the mole would always go to the surface to learn more about what created the vibration.

It is said by the Old People that the mole knows when the cougar is prowling above, just as it knows the approach of a human and the scurry of a rabbit. And that is why the tiny mole is the animal among all animals who commands the greatest amount of respect. Because though the mole might put himself at great danger, the mole always takes the time to investigate what it feels (Wagamese, 2021, pp. 47-49).

“Love your enemies,” Jesus says.

Adversity challenges us to activate the better part of ourselves. Because however you define your enemy within and without, the enemy is an opportunity to reset a relationship, to re-balance things, with ourselves, with others, with creation, and with God.

“Love your enemies,” Jesus teaches us, because in the end, it’s about relationships. We were God’s enemy because humanity killed Jesus. Because sin kept us separated from God. What God did was to break down that barrier of enmity by forgiving us, loving us. Jesus gives us a way to deepen and in the end strengthen relationships of love despite the reality, the imperfection of it all, and the adversity we will always face in this life.

“I used to pray for everything I thought I wanted,” prays Richard Wagamese, “big cars, big money, big … everything. Mostly, so I could feel [big]. That was always a struggle. These days I’ve learned to pray in gratitude for what’s already here: prosperity, health, well-being, moments of joy and to pray for the same things for others …. I’m learning to want nothing but to desire everything and to choose what appears. Life is easier that way, more graceful and I AM [big] – but from the inside out” (Wagamese, 2021).

References:

Burkeman, O. (2024). Meditations for mortals: Four weeks to embrace your limitations and make time for what counts. Penguin Random House.

Wagamese, R. (2021). Richard Wagamese selected: What comes from spirit. Douglas & McIntyre.