See, the day is coming, burning like an oven, when all the arrogant and all evildoers will be stubble; the day that comes shall burn them up, says the Lord of hosts, so that it will leave them neither root nor branch. But for you who revere my name the sun of righteousness shall rise, with healing in its wings (Malachi 4:1-2a).

Jesus says, “When you hear of wars and insurrections, do not be terrified, for these things must take place first, but the end will not follow immediately” (Luke 21:9).

These scriptures can make us feel afraid. We can come away from our bible reading today fearful, scared. Our already heightened sense of foreboding for all the bad things that are happening in the world today is not calmed down by these readings. In fact, these scriptures may serve only to fuel and fan the flames of our terror.

I read recently an interesting fact about our brains. When facing a threat, our brain registers three levels of response in succession. The first response – the first brain mechanism that fires when we are confronted by any threat – is not fight or flight. Whenever we feel threatened, the first level activated by the nervous system, is also not freeze and dissociation. Fight or flight, freeze and numbing, are respectively the second and third responses of the nervous system.

No, the very first brain mechanism that fires when we are threatened, the very first level activated by the brain to the nervous system, is social engagement (Van der Kolk, 2014, p. 82). It is reaching out to others. When we don’t get that, when we miss that first level of reaching out to get the help we need from another person, then the brain trips the second and third activations.

When we read the apocalyptic texts – the end-of-times, doom-and-gloom ones like for today – it makes sense to view these scriptures as messages to a traumatized community of faith that must remain together through their trials.

The follow up question for us, is how can we as people of faith meet the many increasing challenges in our lives in an increasingly hostile and divisive world. What do we do first?

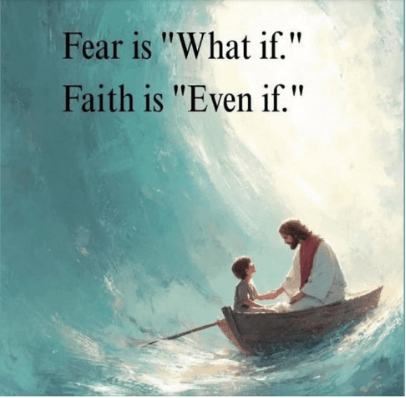

I came across a picture of Jesus sitting in a tiny rowboat with a child. The boat is in the ocean. And coming straight toward them is a towering wave at least ten stories high and just about to crash over them. Jesus and the child are facing each other with a caring, trusting and loving disposition. They’re holding hands.

The caption reads: Fear is: “What if …” Faith is, “Even if ….” “What if” thinking only stokes the catastrophic thinking and anxiety plaguing so many of us today. What if I get sick? What if I make a mistake? What if I miss my opportunity? What if I lose a relationship I cherish? What if I lose my job? What if, What if, What if? “What if” thinking is based in fear and usually creates unhealthy stress and reinforces unhelpful behaviour.

On the other hand, people of faith will practice saying, “Even if”. After all, Jesus says these terrible things “must take place first” (Luke 21:9). It’s not even a question of whether or not, really. Eventually all of us must confront our greatest fears.

So, even if that proverbial wave crashes down over the tiny boat submerging its occupants in the turmoil and crushing weight of water, Jesus goes down with us. Jesus is not afraid to encounter with us our worst fears. Jesus is not afraid to be with us through it all, even dying, because he’s gone through it himself. Our worst-case scenario, he’s been there done that.

So even when the worst thing happens, you will not be alone. Even if you lose everything, you will not be abandoned. Even if your limitations grow and you can no longer function the way you used to, you still have purpose, and you still are loved.

The cross of Christ can enable us to live despite all that challenges us, all the difficulties we face. We gaze on the cross because the story is not over at the foot of the cross.

Our hope is sustained because we are not alone. Being in community creates a larger context for our lives, a meaning beyond our individual fate. We face the proverbial music together.

And I think that’s the point of these scriptures. They are addressed not to individuals, but to communities whose suffering is held together. Recall, that the early followers of Jesus in those first centuries were persecuted and run underground, literally. To survive, those groups of individuals needed to stick together. Given the harsh reality facing people of faith at the time, these texts served as propaganda for their time – a kind of pep talk, motivational piece – aiming to provide solidarity for communities under duress.

I read recently that when the traditional creeds – the Apostles and Nicene – were developed and composed between the 2nd and 4th centuries, that the phrase – “communion of saints” – was the last phrase added to the Creed. The last phrase, why is that? Is it because it took a while for those early Christians to realize how important it was to be in community when facing a personal and collective crisis – of faith, of health, of personal safety? (Rohr, 2025).

In one another’s care, when we make space and hold space for each other’s suffering, that’s where we encounter the living presence of Jesus in our midst. That’s where Christ is present.

I came across a beautiful description of an ancient pilgrimage ritual, “when hundreds of thousands of people would ascent to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, the focal point of Jewish religious and political life in the ancient world.

“The crowd would enter the Courtyard in a mass of humanity, turning to the right and circling – counterclockwise – around the enormous complex, exiting close to where they had entered.

“But someone suffering … the grieving, the lonely, the sick – someone to whom something awful had happened – that person would walk through the same entrance and circle in the opposite direction. Just as we do when we’re hurting: every step, against the current. And every person who passed the brokenhearted would stop and ask: “What happened to you?” “I lost my mother,” the bereaved would answer. “I miss her so much.” Or perhaps, “My husband left.” Or, “I found a lump.” “Our son is sick.” “I just feel so lost.”

“Two thousand years ago, the Rabbis constructed a system of ritual engagement built on a profound psychological insight: when you’re suffering … you show up. You root your suffering in the context of care … You don’t pretend that you’re okay. You’re not okay … the whole world moves seamlessly in one direction and you in another. And even still, you trust that you won’t be marginalized, mocked, misunderstood. In this place, you will be held, even at the ragged edge of life.

“And those who walked from right to left – each one of them – would look into the eyes of the ill, the bereft, and the bereaved. “May God comfort you,” they would say, one by one. “May you be wrapped in the embrace of this community.” “What’s your story? Why does your heart ache?” And after the grief-stricken person answers, you would respond, “I see you, you are not alone.” (Brous, 2024, pp. 3-5).

Our instinct, in facing a threat or some kind of suffering, is to fight, or to retreat, to avoid, to isolate, to hide from others and give up. The tradition of faith, the good parts, are all about resisting those urges and activating what our brain structures are already, naturally wired for.

So, when you meet tough times, if anything, show up. What does showing-up look like for you? It may be faithfully watching the online, weekly services of worship. It may be coming in person to church services every week, once a month, seasonally, or whenever you are able. It may mean asking a friend to drive you to church. However it looks like for you, enter into the spaces and places where people of faith gather. Enter into those places and spaces even if it means swimming against the current.

And if you are not suffering when you go to worship, open your hearts and ears to receive and to validate the stories of those who are. And you will be giving them a great gift.

The gift of Christ’s presence.

References:

Brous, S. (2024). The amen effect: Ancient wisdom to mend our broken hearts and world. Avery.

Rohr, R. (2025). The tears of things: Prophetic wisdom for an age of outrage. Convergent.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin.

Pastor Malina, Beautiful message. I’m still here