You want to start a fire. It’s cold. It’s wet. You’re outside. You need to eat. You need to stay warm. You need to start a fire.

But this fire is in your heart. It may only be a shimmering ember right now, or a small flame at risk of being snuffed out by the winds of despair, depression, disappointment, anxiety, fear or grief. You may feel you never even had that spark in your heart to begin with.

But you want to start. You are willing to try. You want to start up that fire again. But you don’t know how. What are you going to do?

How do we start over? What is our first move on the journey of transformation?

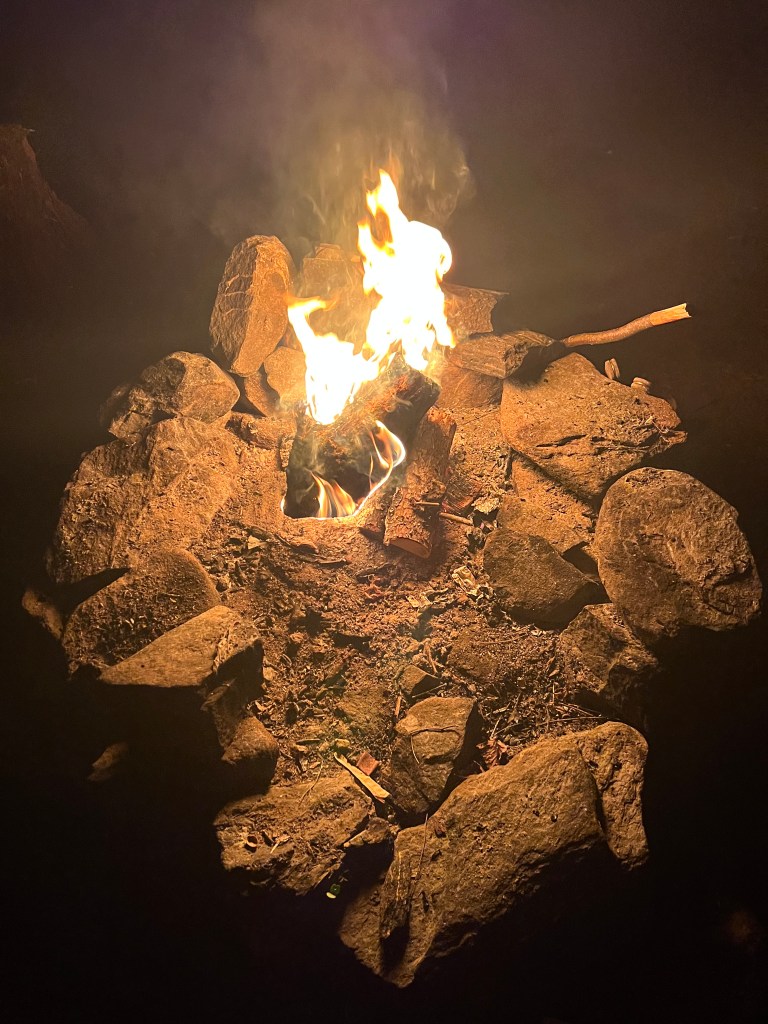

On a backcountry canoe camping trip, my fellow campers and I needed to get and keep a fire going—to cook our meals, to keep warm and to provide the ambiance we all cherish around a campfire. But we did not haul enough wood in our canoes for five days. We needed to start a fire with what we could find on our island site smack dab in the middle of the large Cedar Lake in Algonquin Park.

When campers go looking for firewood, we normally look for hardwood branches, twigs, dry bark. We look on the ground near the campsite for fallen trees and branches. Some campers will even bring saws to cut down trees and chop the wood themselves.

But that strategy was not going to work this time. August, as you may recall, was a wet month—lots of soaking rain. So, most of the wood and trees around us were water-logged, literally. Moreover, it was a very popular spot with the beach—we were fortunate to get it. But that also meant there were precious little scraps of firewood leftover in the immediate area around the site.

We did find something — a kind of combustible material that was plentiful. It’s called fatwood. Stumps from fallen trees covered the island. And some of these had roots still drawing water from the ground up towards the top of the stump. The build-up of sap in fatwood creates chunks of resin. This resin burns like turpentine.

When you burn fatwood, the fire crackles and pops and you don’t get a whole lot of smoke. But best of all, a small piece of fatwood burns for hours, longer than any other kind of firewood! It’s perfect!

Normally we wouldn’t look for dead stumps littering the forest floor to find the combustion we need. The fat wood does not look on the surface like good, burning wood. It is ugly, dirty-looking, wood. Campers usually ignore it, discard it, don’t even see it.

But it was the best thing ever to start and keep a fire going.

To start solving the problem of how to start a fire, we first needed to realize the limits of our usual strategy. We first needed to confess that the way we have normally done things will not work in the present circumstances. They may have worked well in the past and in other contexts. But no longer. The first step towards positive change is to admit we need to approach things differently at the start.

Where are we going to look for a way forward, when we confess the old ways of doing things in our personal lives and in the church no longer work today? Where are we going to look?

The Gospel of Matthew can help. It was written to Jewish Christians who also had to start over. This Gospel was written at the end of the first century right after Roman Emperor Vespasian completely destroyed the temple in Jerusalem. Those Jews who survived the brutal purge were demoralized and uncertain about how to move forward. “There is no known equivalent to what Rome did that day,” one scholar claims.[1]

The Jewish remnant escaped to Antioch in the north. Among them were the Messianic Jews who believed that the Messiah had already come in the person of Jesus, himself a Jew. What help does Matthew’s Gospel offer in a time of upheaval and dramatic change?

First, notice the tone of Jesus’ teaching in the Gospel. Several times in the Gospel of Matthew we hear this paradox from the mouth of Jesus—this tension between apparent opposites of “loosening” and “binding”, of “losing and finding”. It’s not just in our Gospel reading for today, but in at least three other places where we dance on fulcrum of both/and.[2]

Jesus says opposite kinds of things all the time—both comforting AND challenging: “Come to me all ye that are weary and carrying heavy burdens and I will give you rest”[3]; and then: “I have come not to bring peace but a sword.”[4] This Gospel like no other is full of paradox and seeming opposites. Why? To acknowledge the time of transition among first century Messianic Jews: from the pain of loss to the challenge of new beginnings.

Jesus seems to describe a life of faith as one in which we are always leaving something behind and starting something new, letting go of past strategies and learning new ones. It’s admitting that there are times when I have to look elsewhere and not necessarily where I’ve looked before in order to face a challenge.

Then we see Jesus in action as he encounters people on his travels. He meets, for example, the Canaanite woman. She persists and is relentless against Jesus who is rude to her and quite insulting. Because of the woman’s courage to challenge a rabbi, Jesus grants her what she asked—the healing of her daughter.[5]

The old strategy of reaching out only to Jews with the message of Christ needed to change. Our Lord Jesus himself models for us inner transformation, which is the starting point for our journey of faith towards healing and wholeness.

The biggest help Matthew offers, however, is the framing of the Gospel—how it begins, and how it ends:

Matthew begins with the story of Jesus’ birth. And Matthew is the only Gospel of the four that includes the visit of the Magi.[6] These wisdom-seekers from the far East were not Jews. They were Gentiles—using the language of the New Testament.

And, the Gospel concludes with the famous words of Jesus, the great commission to his disciples to go “to all nations” with the news of God’s love and saving promise.[7] “All nations” refers to the Gentiles. The term Gentile refers to people who were outside the pure, Jewish religion.

In the midst of a devastating loss, the Jewish Christians in Antioch were encouraged to engage and be with people outside their tradition. They were called to a journey that Saint Paul would later pick up and emphasize, a journey to include Gentiles in God’s loving embrace, making an ever-widening circle.[8]

Where do we look on the start of our journey of transformation, when we admit old strategies no longer serve us well? The Gospel of Matthew suggests we look beyond the bounds of our own perception which will often blind us to what is right in front of us. The Gospel of Matthew, in modelling for us this shift, suggests we confess our bias, and embrace a new path as yet untrodden.

There’s also a holy part to this journey that yields the warmth, radiance and beauty of a good-burning campfire. And we will discover that, too, along the Way.

The fatwood ain’t pretty. Yet God calls us to this journey of transformation not in spite of but because of the unattractive, broken parts of our lives. There’s something immeasurably valuable about fatwood. The journey will include all of it.

Thanks be to God.

[1] John Alexander Shaia, Heart and Mind: The Four-Gospel Journey for Radical Transformation (Sante Fe New Mexico: Quadratos LLC, 2021), p.74-75

[2] Matthew 10:39; 16:19, 21-28; 18:15-21

[3] Matthew 11:28

[4] Matthew 10:34

[5] Matthew 15:21-28

[6] Matthew 2:1-12

[7] Matthew 28:18-20

[8] Read Paul’s letter to the Galatians, for example. See, also, Matthew R. Anderson’s “The Purists: Laphroaig Single Malt Islay & The Gospel of Matthew” in Pairings: The Bible and Booze (Toronto: Novalis Publishing, 2021), p.89-98